Secret dealings with “Satan”: How the Polish modus vivendi came about

Secret dealings with “Satan”: How the Polish modus vivendi came about

The 1950 Modus vivendi with the Soviet satellite of Poland was the first agreement between the Vatican and a Communist state. Never published in the official gazette, this pragmatic agreement was meant to grant secret concessions which set no precedent. To conduct these negotiations a Joint Commission of government and bishops was set up. This conducts secret meetings even today.

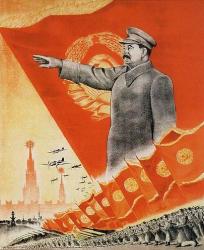

The Joint Commission, formed to negotiate with the

Communists, has been retained as an effective lobbying body.

Here it meets at the bishops’ headquarters in 2006.

By Maciej Psyk

The Vatican’s Ostpolitik – its softly, softly policy with the Communists – was pursued nowhere with greater delicacy than in Poland. In 1949 consultations began between the Government and the Polish bishops, headed by the aged Cardinal Sapieha, Archbishop of Krakow. The Cardinal was an aristocrat who during the war had become “the effective head of the Polish Church after Primate Hlond fled the country”. [1] For the sake of these negotiations, a secret body was formed in 1949, the predecessor of the Joint Commission. [2]

The Vatican professed to find it "incredible"...

The talks had been going on for almost a year when the whole of the Polish Episcopate voted – internally – in favour of the agreement they’d worked out. Then, shortly before the ceremonial signing on 14 April 1950, the aged Cardinal Sapieha was "invited" to visit Rome. While he was away, Archbishop Wyszyński (pronounced “Vishinsky”) quickly concluded the agreement with the Communist regime.

The absence of the top Polish churchman enabled the Vatican to profess shock and surprise. Vatican spokesmen cast doubts in public that the Polish bishops had signed the agreement voluntarily: "It is incredible that an agreement of this scope could have been negotiated without Cardinal Sapieha's knowledge. It could be only a diktat." [3] Naturally the Church didn’t want to admit to having accommodated itself to Communism, which Pius XI had called a “satanic scourge”. [4] Removing the senior Polish Archbishop from the country before the signing allowed the Church to reach an agreement with the Communists, yet claim it hadn’t done so voluntarily.

However, the Church went on for almost 40 years to use this agreement to begin cautiously rebuilding the Church in Poland. Furthermore, Archbishop Wyszyński, who’d ostensibly acted on his own, rather than being disciplined, was three years later promoted to Cardinal.

Sweetening the deal with an escape clause

Cardinal Wyszynski later wrote that "There were significant objections against the modus vivendi. [...] From many parts of the country there were voices of warning addressed to Episcopate and calls to be aware of the finality of the modus vivendi". [5] Yet these were not heeded: strategic considerations prevailed.

Cardinal Wyszynski later wrote that "There were significant objections against the modus vivendi. [...] From many parts of the country there were voices of warning addressed to Episcopate and calls to be aware of the finality of the modus vivendi". [5] Yet these were not heeded: strategic considerations prevailed.

The modus vivendi was signed less than a month after the Communists nationalised Polish Church property in the "central part" of Poland. Yet Articles 2.3 and 7.1 were escape clauses, allowing the Polish Church, at the discretion of the Government, to administer some nationalised land and even to get title to it.

No wonder both sides wanted to keep this quiet: the Church for bargaining with the "satanic scourge" and the Communists for betraying their nationalisation programme. Thus the modus vivendi was not ratified by the Polish parliament (Sejm) and was not even published in the official gazette A few days after signing the accord the Government established an "Office for Confessional Matters" to help it exercise control by censoring sermons and watching for deviations in the ranks of the clergy. [6]

The modus vivendi itself remained full force for less than three years, before being abrogated on 9 February 1953, a month before the death of Stalin. This was done by a Stalinist Decree [7] which violated the Communists’ own 1952 Constitution. The Decree stated that state approval was henceforth required for the Church appointment of key churchmen, including bishops. [8]

The modus vivendi itself remained full force for less than three years, before being abrogated on 9 February 1953, a month before the death of Stalin. This was done by a Stalinist Decree [7] which violated the Communists’ own 1952 Constitution. The Decree stated that state approval was henceforth required for the Church appointment of key churchmen, including bishops. [8]

"We cannot!"

The reply of the Polish Church to the Stalinist Decree was delivered in the memorandum of 8 May 1953 titled Non possumus! (We cannot!) [9]

In the negotiations for the very first Concordat of London Pope Paschal gave the same answer when the English King insisted on naming bishops: “we cannot” allow the request “without offending against God or […] imperiling our salvation and yours” p. 137 It echoes the Biblical phrase “we cannot” (“non possumus”) in Acts 4:20. [10]

However then, as now, this turns out to be just a bargaining tactic. The traditional Spanish and Portuguese privilege of royal patronage “patronato real” was granted by the Catholic Church for centuries. In the Dominican Republic, for instance, the 1884 Convention gave the government the right to name the country's Catholic bishops, as well as veto power over appointments of clergy down to the parish priest level.

So much for the dramatic pathos of “We cannot”, which ended with a “Statement of the Episcopate” claiming that further concessions were not possible, even at the price of martyrdom.

This histrionic assertion did not, of course, prevent up to 15 percent of Poland's churchmen from cooperating with the Communist secret police, situation which was finally exposed in 2007, by the Rev. Tadeusz Isakowicz-Zaleski [11] whose book was delayed for several months by the Church's gag order. [12]

Despite the document's complaints about creeping secularisation, the Church in Poland fared better than it did elsewhere behind the Iron Curtain:

[I]n communist Poland, until 1961, religious classes were not excluded from public school. Even more significant is the fact that the Catholic Church received financial aid from the communist state when the state supported one university-level Catholic school [...]. [13]

The Communist response to the Polish bishops’ “We cannot” was to confine the recalcitrant Cardinal Wyszynski, successively to various convents for the next three years. He saw himself as the “father of the nation”, a religious, moral and even political guide, and when he was imprisoned he was considered a hero and a martyr.

Finally free of Stalin's ghost

Then in 1956 Krushchev's “secret speech” to the Communist leadership launched the de-Stalinisation campaign. Poland's Stalinist government survived the new Soviet policy by only a few months, falling in October 1956. Now the Polish government needed the Church, and Cardinal Wyszynski found himself in a position to dictate the terms on which he would accept his freedom. The implied threat was that if the Cardinal encouraged protests and they got out of control, Soviet tanks might roll over Poland. It was now vital to the Communist government that the Cardinal comply with Article 8 of the modus vivendi that “The Catholic Church…opposes the criminal activity of underground groups”.

The Cardinal’s release was followed on 5 December 1956 by the “Early Agreement” (Małego Porozumienia), a revision of the Stalinist Decree, significantly relaxing restrictions. Government approval was no longer necessary for the appointment of senior churchmen, (however the state still required bishops to make an oath of allegiance to the People’s Republic of Poland), religious instruction was reintroduced in the schools and Catholic journals could be published once more. [14] This agreement remained in force until the Rakowski Act of 17 May 1989 prepared the way for a new concordat.

Summary

The 1950 modus vivendi is divided into two parts. Articles 1-9 state what the Church is granting to the state and Articles 10-19, what the state promises to the Church. The Communists wanted the Polish bishops to recognise them as a legitimate government. They also hoped to secure their support in suppressing the remnant of the anticommunist underground and in opposing the demands of East Germany for what the Poles called the “Recovered Lands/Reclaimed Territories”, (former German territory which came under Polish administration after World War II).

The Church, for its part, received under the label “religious freedom” a wide range of measures which secured its place in Polish society: freedom for public worship, processions, pilgrimage and missionising, the right of association, freedom of action for religious orders, the right to establish chaplaincies in the military, in prisons and in hospitals, to publish books and periodicals, to maintain existing Catholic schools and the Catholic University of Lublin, and to teach catechism in state schools.

The Polish modus vivendi shows what the Catholic Church is able to promise — when it wants to — without abandonning its loyalty to the Pope.

♦ More on the Joint Commission of government and bishops

Notes

1. Dariusz Libionka, “Antisemitism, Anti-Judaism, and the Polish Catholic Clergy during the Second World War, 1939-1945”, Robert Blobaum, ed., Antisemitism and Its Opponents in Modern Poland, (Cornell University Press, 2005), Google print, p. 238.

2. The talks, began on 6 July 1949 in the framework of a “Combined Committee/Commission”, the predecessor of the “Joint Commission” established after the Gomulka shake-up in 1956.

3. "Way of Dying", Time, 24 April 1950. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,812230,00.html

4. Pius XI, Divini Redemptoris, 19 March, 1937. Articles 1-24 describe Communism in terms of the “occult forces […] working for the overthrow of the Christian Social Order” (18). http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/pius_xi/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-xi_enc_19031937_divini-redemptoris_en.html

5. Polish Episcopate, Memorandum of 8 May 1953, Non possumus. http://www.nonpossumus.pl/nauczanie/nonpossumus.php

6. Bernard A. Cook, Europe Since 1945: An Encyclopedia, Taylor & Francis, 2001, Google print, p. 1012.

7. Polish text of the Decree: http://isip.sejm.gov.pl/servlet/Search?todo=file&id=WDU19530100032&type=2&name=D19530032.pdf

Brief English summary of the Decree in Prof. Pierre Buhler, Histoire de la Pologne communiste : autopsie d'une imposture, Paris, 1997, pp. 54. http://coursenligne.sciences-po.fr/pierre_buhler/livre/chapitre3.pdf

8. (This was similar to a law passed in 1790, during the French Revolution, the Civil Constitution of the Clergy.)

9. http://www.nonpossumus.pl/nauczanie/nonpossumus.php

10. Pope Paschal II to Henry I of England, 1101, Eadmer's History of Recent Events in England, ed. G Bosanquet (London, 1964), p.85.

During the protracted negotiations for the Concordat of London, in 1097 Archbishop Anselm phrases his refusal in terms of a Biblical quote (Ibid., p. 85): “for it is written, ‘It is right to obey God, rather than men’.” This and Pope Paschal’s reply are based on Acts 4:18-20

18. Then they called them in again and commanded them not to speak or teach at all in the name of Jesus. 19. But Peter and John replied, “Judge for yourselves whether it is right in God's sight to obey you rather than God. 20. For we cannot help speaking about what we have seen and heard.” (In Latin : 20. non enim possumus quae vidimus et audivimus non loqui).

11. “Priest leads push to expose clergy”, Associated Press, 11 January 2007. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/01/11/AR2007011101330.html

12. “Eurasian Secret services daily review: New book reveals communist spies' ties with Polish clergy”, Axis Information and Analysis, 26 February 2007. http://www.axisglobe.com/article.asp?article=1237

See also Marius Heuser and Peter Schwarz, "Poland: Archbishop's resignation exposes crisis of Catholic Church", World Socialist Web Site, 31 January 2007. http://www.wsws.org/articles/2007/jan2007/pola-j31.shtml

Even the present (1983) update of Canon Law is well designed to enforce secrecy and to rein in any clerical whistle-blowers. For instance, Canon 1339 §2 forbids "behaviour which gives rise to scandal" (for the Church, of course) and Canon 1390 §2 forbids a cleric to "injure the good name of another".

13. Krystyna Daniel, "The Church-State Situation in Poland After the Collapse of Communism", Brigham Young University Law Review, Vol. 1995 (2, 1995). 401-420. http://religlaw.org/docs/religlaw_1254.pdf

It is not true that, as Daniel maintains, the state "paid salaries for teachers of religious classes (since 1961)". The Church rejected this attempt to turn priests into state functionaries.

14. Cook, ibid.