Some Colombian concordat summaries

Some Colombian concordat summaries

Colombia's first concordat (1887) returned to the Church much of the power it had enjoyed in the colonial period, including the right to administer “mission territories” which comprised more than 60 percent of the country. The standard work in Spanish details all the concordats up to 1988: here are a few summaries in English from the web that show how Church and state were interwoven in Columbia.

The Núñez Concordat (1887)

The Núñez Concordat (1887)

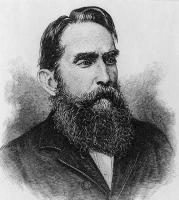

Colombia's first concordat is named after Rafael Núñez, the dictator who abrogated the secular 1863 Constitution and then excluded his political opponents when drafting a replacement. His new 1886 Constitution proclaimed that “the Apostolic Roman Catholic Church is that of the Nation” and provided for the negotiation of a concordat with the Papacy. The next year Núñez signed the concordat. [1]

Over a century later the same thing was done in Poland, when the 1997 Constitution was adjusted to permit ratification of the concordat the next year. The reference to the separation of church and state in the previous Polish constitution was replaced with “the mutual independence of each in its own sphere”. This is not quite as obvious as the wording of the new Colombian constitution, but it had the same effect.

This Colombian constitution remained in force for over a century and during that time protected not only the Núñez Concordat, but also its successors. Only under the Consititution of 1991 did concordat challenges finally become possible .

Excerpt from Daniel Levine [2]

Until 1973, a concordat (originally negotiated in 1887) set the terms of the Church’s legal status and role. This agreement is a model of the traditional ideal of “Christendom” – complete Church-state integration. The Church is described as “an essential element of the social order” and given a major role in many aspects of social life. For example, education at all levels was to be maintained “in conformity with the dogma of the Catholic religion" and religious instruction was obligatory. The Church also received a predominant position in the registry, with parish records having preference over civil records. In addition to the registry of birth, the management of death was placed in Church hands, as cemeteries were turned over to the ecclesiastical authorities.

Marriage, another major step in the life cycle, was also firmly under Church control. Civil divorce did not exist, and civil marriage for baptized Catholics was contingent on public declarations of abandonment of the faith. These statements were to be made before a judge, posted publicly and communicated to the local bishop. It is difficult to imagine a more effective mechanism of ostracism, or a more telling example of the fusion of civil and religious powers than these arrangements (cf. Jaramillo Salazar).

Finally, the Church wields broad civil powers in the more than 60 percent of Colombia’s area designated as “mission territories”. Here, a 1953 agreement gave the missionary orders extensive control over education as well as broad civil powers. The concordat and additional accords clearly left many areas of Colombian life to Church control and management.

The Echandía-Maglione Concordat (1942)

The 1942 revision of the concordat gave the Vatican more power in the naming of bishops. This was in line with the Vatican’s use of concordats to end the Latin American tradition of state control over Church appointments, inherited from the Spanish king’s “patronato real” (royal “patronage”, i.e., privilege). However, overall this concordat somewhat relaxed Church control and was fiercely opposed on that account.

Excerpt from Thomas J. Williford [4]

[In April 1942,] on the eve of the presidential election, Darío Echandía [Colombia's ambassador to the Vatican] had concluded a concordat with the Vatican after five years of negotiations. […] When it was initially signed, the concordat was effusively supported by the Vatican, which saw it as a model for other treaties with Catholic countries around the world. […]

The new concordat treated relatively mundane issues: all matrimonies would have to be registered with the government and cemeteries were to be under the jurisdiction of municipalities rather than parishes. Early on in the negotiations, Echandía had decided to abandon what most anticlerical Liberals had wanted most: the excision of Church tutelage from public instruction. Church influence would remain in establishing official curricula for all schools in the country.

Additionally, under the new treaty, the Vatican would name Colombian-born bishops, with the government reserving the right to reject a bishop for political reasons. Previously, the 1887 concordat had Colombian presidents send a list of possible candidates for open bishoprics to the Vatican, thus the new agreement actually gave more power to the Holy See in this matter. As even El Siglo [a rightwing newspaper] pointed out in April 1942, the new procedure for naming bishops was the same as in the concordats that the Holy See had signed with Franco's Spain, Mussolini's Italy, and Hitler's Germany.

The Vázquez-Palmas Concordat (1973)

The Vázquez-Palmas Concordat is named after its two signatories, the Colombian Foreign Minister and the Papal Nuncio. Two summaries are given below: an overview from the Library of Congress' excellent Country Studies and a detailed summary by the Colombian Goverment.

Excerpt from Country Studies [5]

The concordat [of 1973] replaced the clause in the Constitution of 1886 that had established the Catholic Church as the official religion with one stating that "Roman Catholicism is the religion of the great majority of Colombians." The concordat also altered the church's position on three major issues: the mission territories, education, and marriage.

♦ First, the mission territories — lands with Indian populations — ceased to be enclaves where Catholic missionaries had greater jurisdiction than the government over schools, health, and other services; by agreement the vast network of schools and social services was eventually to be transferred to the government.

♦ Second, the Church surrendered its right to censor public university texts and enforce the use of the Catholic catechism in public schools. Under the new concordat, the Church retained the right to run only its own schools and universities, and even these had to follow government guidelines.

♦ Finally, Colombians were allowed to contract civil marriages without abjuring the Catholic faith. The civil validity of Church weddings was also recognized, although all marriages were also to be recorded on the civil registry. Catholic marriages, however, could only be dissolved through arbitration in a church court.

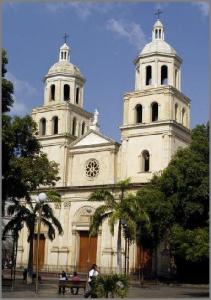

Despite these changes, the tenacity of custom and the Church's traditional position as a moral and social arbiter ensured its continued strong presence in national life. The parish church still was recognized as the centre of nearly every community, and the local priest was often the major figure of authority and leadership. […]

The influence of the church varied in different regions of the country and among different social groups, but it was felt everywhere and was rarely questioned.

Summary of the 1973 concordat by the Colombian Government [6]

Summary of the 1973 concordat by the Colombian Government [6]

(a) It does not proclaim an official religion. The State merely declares that it regards the Catholic religion as being of “fundamental importance to the public welfare and the full development of the community”;

(b) The new concordat substantially retains the provisions of the 1887 Agreement concerning recognition by the State of the Church’s spiritual authority, legal personality and capacity to collect offerings and contributions from its followers;

(c) The State accords Catholic marriage — i.e., “marriage celebrated in accordance with the norms of canonical law” — full recognition for civil purposes, but does not make it obligatory;

(d) Bishops — and persons canonically assimilated to them — are granted immunity in criminal matters identical in scope to that extended to diplomatic agents;

(e) Members of the clergy and religious orders enjoy a degree of privilege in criminal proceedings instituted against them by the Commission of Non-Ecclesiastical Offences;

(f) The Church undertakes to give the president of the Republic advance confidential notice of Episcopal appointments with a view to ascertaining whether he has “civil or political objections” to the candidates;

(g) The State acknowledges the Church’s freedom of instruction and independence to organise and run faculties, institutes, seminaries and a training establishment for religious orders;

(h) The State undertakes to make a reasonable contribution to the maintenance of Catholic educational establishments and to include courses of religious instruction in its primary and secondary curricula;

(i) Church and State undertake to co-operate in the social advancement of indigenous persons and other inhabitants of what were formerly known as “mission territories”;

(j) The financial obligations acquired by the State by virtue of the Núñez Concordat [1887] and the Missions Agreement of 1953 are consolidated.”

Sources

1. Hugh Hamill, Ed., Caudillos: Dictators in Spanish America,1995, pp. 161-62. Google reprint

2. Levine, Daniel. “Church Elites in Venezuela and Colombia: Context, Background, and Beliefs”. Latin American Research Review, 14.1 (1979), p. 55. Quoted at “Posición extraordinaria de la iglesia”. http://www.ensayistas.org/critica/liberacion/casadont/posicion.htm

3. Laureano Gómez: "Yo hablo -dijo en 1942 en el Senado-, en nombre de los principios de la doctrina católica, que están expresados en las obras filosóficas de Santo Tomás, que dice cómo debe organizarse un Estado". This is much quoted online, e.g., http://www.revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/recs/article/viewFile/11175/11840

4. Thomas J. Williford, Armando los espiritus: Political Rhetoric in Colombia on the Eve of La Violencia, 1930-1945, 2005, pp. 211-212. http://etd.library.vanderbilt.edu/ETD-db/available/etd-07222005-085639/unrestricted/WillifordFChap4.pdf

5. Dennis M. Hanratty and Sandra W. Meditz, ed., Colombia: A Country Study. Washington: Library of Congress, 1988. http://countrystudies.us/colombia/51.htm

6. Quoted in Edward H. Lawson and Mary Lou Bertucci, Encyclopedia of human rights, Edition: 2, 1996, p. 264. Google reprint