%%rimage[India's secularist ideal under threat]=X1551_727_INFlagBirdLogo_t55.jpg India's secularist ideal under threat

Is India in the process of being turned from a secular state into a Hindu one? The greatest threat to religious freedom in India today are the moves to strip Indian Muslims ofmany of their rights, including citizenship. If the massive protests by Indians from all religious backgrounds do not persuade the Hindu nationalist government to change course, Indian secularism will be finished. No matter what the constitution says, India will effectively become a single-religion state like some of its Muslim neighbours.* However, this pressing issue is too fast-moving to be treated here.

“Communal”, not just “religious”

In a huge country with diverse regions, ethnic groups, languages, castes and stark rural-urban divides it's simplistic to talk only about “religious” differences. Indians wisely prefer to speak of “communal” ones:

It is often incorrect to link a violent incident to religion alone, at least in India’s case. In India, we use the word “communal” – as opposed to “religious” – to suggest that the motives could range from a clash of worldly interests to the political targeting of one community. In fact, though communal violence does pit one religious group against the other, political disagreements are the most prevalent cause of such violence.[1]

The anti-conversion laws versus the Constitution

India's secular constitution is undermined by the "Personal Law" that governs family life according to one's religion. And there are other laws which may conflict with constitutional guarantees of religious freedom. These are the anti-conversion laws that ban religious conversion through force, "allurement" or fraud. Thesehave been targeted at two groups, foreign Christian missionaries, and members of India's own Muslim minority.

There has long been resentment in India against Christian missionaries from abroad who "buy" converts in the middle of a famine. [2] Yet attempts to curtail this can interfere with Article 25 of the Constitution which guarantees "freedom of conscience and the right freely to profess, practise and propagate religion".

Even today, among the tribal peoples of Jarkhand mass conversions are performed, from Hinduism to Christianity or vice versa. Although many wish to keep their own animistic beliefs, desperate poverty can make the offer of rice, milk and a free education irresistible. Only later do some discover that six months after baptism, they will have to pay school fees, after all. As one woman said, she is so poor that all she has left to sell is her religious identity. [3] It can hard to maintain religious freedom when other human rights are not being met.

This is the reason for the anti-conversion laws in some of the Indian states. [4] They prohibit religious conversion obtained through the use of force, "allurement" or fraud and forbid anyone to aid these illegal conversions.

However, out of respect for India's constitutional guarantee of religious freedom, anti-conversion laws have not been passed by the national government. And there are also problems with their implementation by the states. This places their enforcement in the hands of local authorities in communities which may be divided along religious lines. And the wording of these laws is so general - they prohibit "inducement or allurement" - as to give the authorities much scope in interpreting them. [5] Furthermore, such laws have not stopped the forcible re-conversion of thousands of Christians back to Hinduism. [6]

In 2012 there was a successful challenge of the anti-conversion law of one Indian state, leading to some parts if it being declared unconstitutional. In the northern Indian state of Himachal Pradesh the High Court declared that religious freedom must include not only "the right to change faith, but also has the right to keep secret one's beliefs". [7] This struck down that state's rules which made free conversion from one religion to another illegal unless it was preceded by a long process, including investigation and authorisation by a magistrate.

However, popular support for the anti-conversion laws has been whipped up by Hindu Nationalists who have spread a conspiracy theory called the Love Jihad. This is the unfounded idea that Muslims are plotting to replace Hindus by luring Hindu women into marriage. Despite its absurdity, this theory has wide appeal, since it also bolsters traditional arranged marriages. It provides Hindu parents with a convenient way to regain control of a daughter who has chosen a love marriage, if it happens to be with a Muslim. And in one state, even the Catholic Church has helped to fuel the paranoia and resulting persecution. In 2009 Kerala Catholic Bishops Council (KCBC) called Christians, as well, to be on guard against the threat to their daughters from this (imaginary) Muslim plot.

In the midst of this religious hate campaign, Oommen Chandy, the distinguished First Minuister of Kerala, spoke out. He said that there was no evidence of forced conversions in the state and that the fears about love jihad were baseless. "We will not allow forcible conversions. Nor will we allow to spread hate campaign against Muslims in the name of love jihad." [8]

The struggle to modernise religious law

An even more fundamental conflict with the secular constitution lies in the "Personal Law" which prescribes different rules for members of various religions in areas like marriage, divorce and inheritance. For in India there is no law code that applies to everyone in every area of life.

Such a "Uniform Civil Code" (UCC) was impossible to achieve during the colonial period due to the British policy of indirect rule by which they relied upon local rulers and religious leaders. However, after Independence, a uniform civil code became the goal of the first Prime Minister of the Indian republic, Jawaharlal Nehru, his supporters and women members of his Congress party. Today some Indians continue to argue for a secular law for everyone in all areas of life, [9] not just a uniform criminal code. [10]

Yet even more than 70 years later there seem to be no realistic prospects of this happening any time soon. Instead, there are still special laws for people of various religions which keep their personal affairs under the control of the religious authorities and local custom.

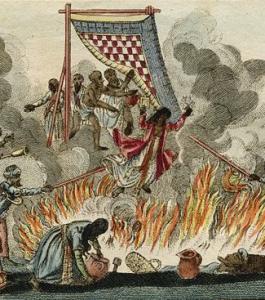

Changing these laws has proven to be easier for the Hindu majority than for India's largest minority, the Muslims. The modernisation of the laws regarding Hindus started with the abolition of the sati, the religious and social obligation of a widow to be burnt to death on her husband's funeral pyre. This was first banned in 1829 by a British Governor of the East India Company and a Bengali reformer, after his own sister-in-law had been burnt to death.

Changing these laws has proven to be easier for the Hindu majority than for India's largest minority, the Muslims. The modernisation of the laws regarding Hindus started with the abolition of the sati, the religious and social obligation of a widow to be burnt to death on her husband's funeral pyre. This was first banned in 1829 by a British Governor of the East India Company and a Bengali reformer, after his own sister-in-law had been burnt to death.

Ending this practice then raised the problem of what to do with these widows. In the higher Hindu castes where child marriage was practised and remarriage prohibited, this led to a lifetime of misery:

Irrevocably, eternally married as a mere child, the death of the husband she had perhaps never known left the wife a widow, an inauspicious being whose sins in a previous life had deprived her of her husband, and her parents-in-law of their son, in this one. Doomed to a life of prayer, fasting, and drudgery, unwelcome at the celebrations and auspicious occasions that are so much a part of Hindu family and community life, her lot was scarcely to be envied. [11]

The Hindu Widows' Remarriage Act of 1856, passed during the British Raj (1858–1947), was designed to give these women a second chance. Further measures followed, such as the Married Women's Property Act of 1874, which was created to protect the properties owned by women from relatives, creditors and even from their own husbands. [12] A bundle of post-Independence government measures, the Hindu Code Bills (1955), carried this process further. And Hindu Personal Law was also modernised by compliance with the the Child Marriage Restraint (Amendment) Act 1978 which requires brides to be least 18 years of age.

But what of the Muslim women? Indian Muslims are poorer and less educated than average and Muslim women have less access to contraception. [13] They are also still governed by colonial-era acts which put them under Muslim civil law, in other words, that part of Sharia that does not involve “criminal” offenses. These are the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act (1937) and The Dissolution of Muslim Marriage Act (1939). Under the first, Muslim women can still be married off as children, be obliged to share a husband with other wives and have their marriage ended if the husband tells them three times, "I divorce you".

This law was meant to be implemented by a group made up mostly of clerics, the All India Muslim Personal Law Board. However, it has been accused of trying to defeat the purpose of the two laws relating to Muslims, by setting up a parallel court system. [14] The Muslim Board also opposes gay rights, free and compulsory education for children, the ban on child marriages and any change to the marriage laws that would empower women, including even the demand by women’s groups that marriages be legally registered, as is mandatory for non-Muslims. [15]

To try to get around the immoveable Muslim Board, in 2014 a group of Muslim women, the BMMA, presented a proposal for a redrafting of the Personal Laws relating to Muslims in India. [16] They worked on the draft for seven years, spending two of these talking to Muslim women, most of them poor, uneducated and living in ghettos. It was these women who were desperate for a change, urging the BMMA to “quickly change the law, get us justice.” [17]

Poverty and patriarchy

In 2013 India refused to sign the first-ever global UN resolution on early and forced marriage of children. Despite India's constitutional secularism, even in the 21st century the country holds the record of the highest absolute number of child brides: about 24 million wed under the age of 18. This represents 40% of the 60 million world's child marriages. [18]

In 2013 India refused to sign the first-ever global UN resolution on early and forced marriage of children. Despite India's constitutional secularism, even in the 21st century the country holds the record of the highest absolute number of child brides: about 24 million wed under the age of 18. This represents 40% of the 60 million world's child marriages. [18]

Of course, under Muslim Personal Law, some of this this is perfectly legal. However, there are huge numbers of Hindu child brides, too, despite the fact that the present Hindu Personal Law should ensure that brides are at least 18 years of age. Especially in rural areas, the law can collide with economic necessity and tradition.

The marriage of a minor girl often takes place because of the poverty and indebtedness of her family. Dowry becomes an additional reason, which weighs even more heavily on poorer families. The general demand for younger brides also creates an incentive for these families to marry the girl child as early as possible to avoid high dowry payments for older girls.

The girl in our patriarchal set up is believed to be parki thepan (somebody’s property) and a burden. These beliefs lead parents to marry the girl child. In doing so, they are of course relieving themselves of the ‘burden’ of looking after the child. The girls are considered to be a liability [...] Unfortunately, the patriarchal mindset is so strong that the girl has no say in decision making. Texts like Manu Smirti which state that the father or the brother, who has not married his daughter or the sister who has attained puberty will go to hell are sometimes quoted to justify child marriage. Child marriages are also an easy way out for parents who want their daughters to obey and accept their choice of a husband for them.

There is also a belief that child marriage is a protection for the girls against unwanted masculine attention or promiscuity. In a society which puts a high premium on the patriarchal values of virginity and chastity of girls, girls are married off as soon as possible. Furthermore securing the girl economically and socially for the future has been put forth as a reason for early marriage. [19]

These child brides can lead lives of constant abuse and inconceivable misery, "Child marriage does not constitute a single rights violation - rather, [it] triggers a continuum of violations that continues throughout a girl's life." [20] It can lead to lasting injuries while trying to produce an unlimited number of sickly, malnourished, premature babies, and it is often accompanied by domestic violence, sexual exploitation, lack of education, isolation and total dependency on their oppressors. [21]

The ending human rights abuses is the real meaning of the separation of state from church, temple or mosque.

Indian's neighbours

Pakistan rejected outright the Indian Ideal of secularism. The country's founder, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, said that

Islam is not merely confined to the spiritual tenets and doctrines or rituals and ceremonies. It is a complete code regulating the whole Muslim society, every department of life, collective[ly] and individually. [22]

He felt that Hindus and Muslims were so different that

to yoke together two such nations under a single state, one as a numerical minority and the other as a majority, must lead to growing discontent and final destruction of any fabric that may be so built for the government of such a state. [23]

However, founding an overwhelmingly Muslim state did not prove to be the solution for religious tensions. There has been sporadic violence between the majority Sunni Muslims, the minority Shias and the Ahmadis who, in a 1974 constitutional amendment, were defined as non-Muslims — despite what they themselves maintain.

To their credit the founders of India, although devout Hindus, had a broader vision and, despite sectarian tensions, India has held together. In fact, this success inspired the former East Pakistan, when it gained independence, to aim for secularism, too, even though most of its citizens are Muslim. In its first post-independence constitution in 1972 Bangladesh proclaimed its commitment to secularism. Unfortunately this was dropped by military rulers who came to power through a coup and allied themselves with the Islamists. In 2010 the Supreme Court declared that the military rule was unconstitutional and as was the amendment introduced to allow religious political parties to flourish. [24] However, the sectarian legacy of dictatorship is proving hard to reverse completely. Although in 2011 the Bangladeshi parliament restored secularism as a state principle, it has retained Islam as the state religion. [25]

Notes

* Freedom in the World 2020, A Leaderless Struggle for Democracy, pp. 2-3

https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2020-02/FIW_2020_REPORT_BOOKLET_Final.pdf

1. Vishal Arora, Avoiding four religion-reporting traps, The Media Project, 2011-05-02. http://www.themediaproject.org/article/avoiding-indias-religion-reporting-pitfalls

2. Mohandas K. Gandhi, Harijan, 1937-11-05. http://hvk.org/archive/2008/0108/196.html

3. Raksha Kumar, "The Politics of Religious Conversions in Jharkhand", New York Times, 2013-10-01. http://india.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/10/01/the-politics-of-religious-conversions-in-jharkhand/

4. Niyogi Committee Report, Government of Madhya Pradesh, 1956. http://www.voiceofdharma.org/books/hhce/Ch17.htm

5. American Center for Law and Justice, "'Religious Freedom Acts': Anti-conversion laws in India", 2009-06-29. http://media.aclj.org/pdf/freedom_of_religion_acts.pdf

6. "India under fire over Christian rights", BBC News,1999-09-30. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/461380.stm

7. "Indian Court Suppresses Part of Anti-conversion Law", Zenit, 2012-09-03.

http://www.zenit.org/article-35494?l=english

8. "Over 2500 women converted to Islam in Kerala since 2006, says Oommen Chandy", India Today, 2012-09-04. http://indiatoday.intoday.in/story/love-jihad-oommen-chandy-islam-kerala-muslim-marriage/1/215942.html

9. Nandini Chavan and Qutub Jehan Kidwai, Law Reforms and Gender Empowerment: A Debate on Uniform Civil Code, 2006, p. 11ff. http://books.google.co.in/books?id=0HNgJuBaSfkC&lpg=PP1&pg=PA11#v=onepage&q&f=false

10. "Muslim personal law can't override criminal law: Court", Press Trust of India, 2013-09-23.

http://ibnlive.in.com/news/muslim-personal-law-cant-override-criminal-law-court/424514-3-244.html

11. Lucy Carroll (2008). “Law, Custom, and Statutory Social Reform: The Hindu Widows' Remarriage Act of 1856”. In Sumit Sarkar, Tanika Sarkar (editors). Women and social reform in modern India: a reader, p. 79.

12. “Power to women and children! Life Insurance and Married Women's Property Act”, Times of India, no date. http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/insure-your-health/Power-to-women-and-children-Life-Insurance-and-Married-Womens-Property-Act/starhealthshow/18166650.cms

13. “Indian Muslims Need Greater Access To Education To Avoid Poverty And Social Exclusion”, International Business Times, 2014-03-15 http://www.ibtimes.com/indian-muslims-need-greater-access-education-avoid-poverty-social-exclusion-1561601

14. "Shut Muslim personal law courts, says PIL", Times of India, 2014-07-14. http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/Shut-Muslim-personal-law-courts-says-PIL/articleshow/37988282.cms

15. Nilanjana S. Roy, “Muslim Women in India Seek Gender Equality in Marriage”, New York Times, 2012-04-24 http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/25/world/asia/25iht-letter25.html

16. “Muslim women’s group seeks abolition of triple talaq”, The Hindu, 2014-10-07 http://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/chennai/chen-society/muslim-womens-group-seeks-abolition-of-triple-talaq/article6668378.ece

17. “No second wife, please”, The Hindu, 2014-06-29

http://www.thehindu.com/features/magazine/no-second-wife-please/article6158039.ece

18. “On world stage, India lets down its child brides”, TNN, 2013-10-14 http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/On-world-stage-India-lets-down-its-child-brides/articleshow/24108817.cms

19. Law Commission of India, Proposal To Amend The Prohibition of Child Marriage Act 2006, and Other Allied Laws, Report No. 205, 2008-02-05 http://lawcommissionofindia.nic.in/reports/report205.pdf

20. “On world stage, India lets down its child brides”, TNN, 2013-10-14 http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/On-world-stage-India-lets-down-its-child-brides/articleshow/24108817.cms

21. Law Commission of India, Proposal To Amend The Prohibition of Child Marriage Act 2006, and Other Allied Laws, Report No. 205, 2008-02-05, pp. 18-22 http://lawcommissionofindia.nic.in/reports/report205.pdf

See also: International Center for Research on Women (ICRW), “Child Marriage Facts and Figure”, http://www.icrw.org/child-marriage-facts-and-figures

22. Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Eid message, September 1945. http://forum.urduworld.com/f93/quaid-e-azam-muhammad-ali-jinnah-350585/index4.html

23. Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Presidential Address, Lahore, March 22-23, 1940. http://forum.urduworld.com/f93/quaid-e-azam-muhammad-ali-jinnah-350585/index4.html

24. “Bangladesh court bans religion in politics”, AFP, 2010-07-29. http://www.google.com/hostednews/afp/article/ALeqM5h_5T_bgbToWaGqK2gxXACMFuySog

25. Haroon Habib, “Bangladesh: restoring secular Constitution”, The Hindu, 2011-06-25. http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/article2132333.ece