Napoleon’s concordat lives on in Alsace-Moselle and the Kaiser gave it another one

In Alsace-Moselle, beside the German border, the state pays the salaries of the clerics and the expenses of their churches. Although this border area was twice conquered by Germany and then returned to France, an excuse was always found to maintain Napoleon’s concordat. This concordat has been used to justify further ones. In 2013 it was upheld by the French Constitutional Court.

In the northeast corner of France crucifixes are found in public buildings, clerics are “Category A” civil servants and the state pays their salaries, pensions and unemployment insurance (Assedic). The French taxpayer also covers the administrative costs and upkeep of the church buildings.

In the northeast corner of France crucifixes are found in public buildings, clerics are “Category A” civil servants and the state pays their salaries, pensions and unemployment insurance (Assedic). The French taxpayer also covers the administrative costs and upkeep of the church buildings.

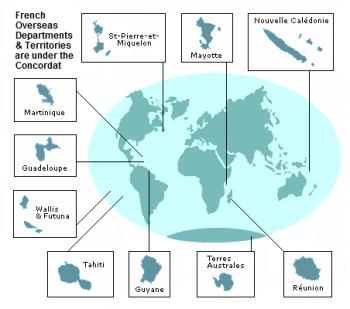

All this is because in this northeastern corner of France Napoleon’s concordat with the Vatican lives on (as it does in the remnants of the French Empire around the globe). Even two German occupations of Alsace-Moselle failed to free it from the French concordat. After 1871, when Germany failed to repudiate the concordat, it continued in force, and in 1941 when Germany did cancel it, it still remained in force, ostensibly because Alsace-Moselle possessed a self-styled government-in-exile in Algeria. It seems that an argument can always be found for keeping a concordat.

How Napoleon’s concordat survived

(Translated from Le livre noir des atteintes à la laïcité, 2006, pp. 41-43)

Concluded in 1801 between the First Consul [as Napoleon then styled himself] and the Vatican, the Concordat appears to be an international treaty. However, it was enacted at the same time as the Organic Articles, a unilateral act of the French Government. Together they are known as the Law of 18 Germinal, Year X. The brevity of the Concordat is matched by the detailed nature of the Organic Articles. These establish state prerogatives affecting the clergy: methods of communication with the Holy See; the appointment procedure for bishops, territorial organisation [of the Church]; the right of the civil authorities to ratify religious decisions; an obligation to spread Gallicanism [independence from papal administrative control over national churches]; police coordination of worship and religious events. The Law of 18 Germinal Year X was later supplemented by additional Organic Articles about Protestant denominations (Reformed Church [Calvinist] and Church of the Augburg Confession [Lutheran]) and Judaism (Decree of 17 March 1808 amended by the Ordinance of May 25, 1844).

In 1870, when Alsace and Moselle came under the sovereignty of the German Empire [...] the Concordat should have been regarded as lapsed, according to a general principle of international law [that a treaty no longer holds if there has been a fundamental change of circumstances]. In fact, the Vatican reached this conclusion at first and then [only later] claimed that the 1801 treaty with the Holy See, signed by the First Republic in its final years, continued in force, so that the French obligations to the religions were assumed by the German Empire. Since Germany did not challenge this second analysis, the Concordat was considered tacitly maintained.

A similar legal debate took place in 1919, when French sovereignty was recovered by the three eastern departments. [These are the Upper Rhine and Lower Rhine (all of Alsace) and Moselle (the north-eastern part of Lorraine)]. For obvious political reasons this time the retention of the concordat was given a different justification. At first, the claim that the concordat had lapsed was countered by another well-established principle of international law: insofar as Alsace and Moselle had been annexed and the State which had conquered them had not renounced the Concordat, the agreement would have been maintained after the return of French sovereignty. Finally, it was stated that because the Treaty of Versailles [giving Alsace-Lorraine back to France] had implicitly repealed the Frankfurt Treaty of 1871 [ceding Alsace-Lorraine to Germany], the French Republic resumed in 1919 the previous circumstances sufficiently that the Concordat of 1801 remained in force. [For this argument] it was essential to maintain the continuing legal jurisdiction of the government of national unity after World War I, while at the same time showing that the German occupation was an interlude with no consequences.

At the time of the next annexation of Alsace-Lorraine at the beginning of World War II, the Nazi regime revoked the Concordat of 1801 and the Organic Articles. However, the Council for the affairs of Alsace-Lorraine of the Provisional Government in Algeria considered that the legal system of the Concordat remained in force. The law of 15 September 1944 restoring the republican laws in Alsace and Moselle, revived the Concordat and Organic Articles, which had been concluded in 1801 and revised in 1808.

Since then, the system of recognised religions applies in the Departments of the Upper Rhine, Lower Rhine and Moselle. In practice, this means the following arrangements: the appointment of bishops by the pope with, in practice, veto power by the French Government; [state] approval of priests, a formal procedure that does not constitute a real constraint for the Catholic Church; making churches and cathedrals available to the clergy; pay for bishops and priests, who are classed as civil servants. Religions are administered by public institutions endowed with legislative bodies, the special parish councils concerned with church finances and property (conseils de fabrique). For the Protestant and Jewish faiths, the same principles apply. The clergy are paid according to a lower pay scale than the bishops. The parish councils (conseils presbytéraux) and consistories are legally responsible for the management of these religious bodies.

Two more concordats hitch a ride

Finally, the Concordat of 1801 serves as the basis for two agreements on the training of theologians: the Convention of 5 December 1902 concluded between the Vatican and Baron von Hertling setting out the management and funding of the Faculty of Theology of Strasbourg, which was created by German [the Kaiser’s] authorities in 1872, and the Agreement of May 25, 1974 signed between the French Republic and the Holy See, extending the 1902 agreement to the Autonomous Centre for Teaching Religious Education (Centre Autonome d’Enseignement de la Pédagogie Religieuse) of the University of Metz.

The 1974 agreement is an important addition to the concordat, because religious instruction is part of school curriculum in both public and private schools. [It is an opt-out requirement and thus] in order to avoid religious instruction both parents and teachers must apply for an exemption. In most cases, religious education is provided by members of the clergy. According to recent statistics, student participation in religion classes is in free fall.

A secular university is merged with a university under the concordat

(Translated from L’Etat fusionne université publique et université catholique, Le Post, 1 September 2010)

A new university was formed in 2011 by merging three universities in Nancy with the one in Metz. The university in Metz has a theological institute which is bound to the Vatican by a concordat and called the Autonomous Centre for Teaching Religious Education.

A new university was formed in 2011 by merging three universities in Nancy with the one in Metz. The university in Metz has a theological institute which is bound to the Vatican by a concordat and called the Autonomous Centre for Teaching Religious Education.

This merger will have serious consequences, for the secular nature of the new university. Indeed, the University Paul Verlaine of Metz, established [in 1970] in the concordat zone, has a department of theology, called the Autonomous Centre for Teaching Religious Education (Centre Autonome d’Enseignement de la Pédagogie Religieuse), part of the Faculty of Humanities and Arts which and answers to both the diocese and the University of Metz. And yet this department offers the complete cycle of Licence, Master and Doctorate in Theology. It is for people who are preparing to teach religion and for future Priests of Lorraine, and anyone who wants training in Christian theology. On the website of the Catholic Church, we read that “most of the courses are held at the University of Metz, within the framework the Autonomous Centre of Teaching of Religious Education, which amounts to the ‘Department of Theology’ of the Faculty of Arts and Humanities.”

But in the preparatory document for the merger we learn that there would be "total fusion of all faculties concerned to make only a general faculty which could for example be called the “Faculty of Humanities”. Nowhere in this document appears an officially named department of theology. Is this an attempt to hide the integration of the religious department in violation of the separation of church and state?

We also learn that “The department heads would be invited to participate in the faculty boards so that they can be the voice of their department and be better informed.” Thus, the religious authorities, through the leadership of the department of theology could give their views on the budget of the whole Faculty of Art and Humanities and on applications for positions, as is stipulated in this document. And so in such a university, representatives of a church could intervene in areas of research, and teaching of other disciplines that are not of the Catholic religion.

* Francis Messner (Director of Research, CNRS, Centre “Religion, Droit et Société en Europe”, Strasbourg), “La création d’une faculté de théologie musulmane : aspects juridiques”, Actes de la journée d'études organisée par le Club Témoin (Bas-Rhin) le 13 juin 1998 à Strasbourg, en collaboration avec le GERI et l'ACFTMS, Strasbourg, 2000. http://www.persocite.com/geri-islam/messner.htm

Napoleon's concordat and Organic Articles (1801): texts and commentary

Napoleon's concordat and Organic Articles (1801): texts and commentary