How Caritas and the Diakonisches Werk began

Catholic charities were expanded by laymen as part of the Counterreformation. However, the first centralised German church charity was established by the Protestants as a response to the threat posed by the socialist workers' movement. Its Catholic counterpart was only permitted as a decentralised organisation of local associations, each under a local bishop.

By Dr. Carsten Frerk, author of Finanzen und Vermögen der Kirchen in Deutschland (2002) and Caritas und Diakonie in Deutschland (2005)

Below are the historical sections of Dr. Frerk's essay, the rest of which is posted as

German taxpayers subsidise 98% of faith-based social services

In 1576 the Würzburg Prince-Bishop Julius Echter von Mespelbrunn founded, according to its charter, an endowment “for the poor, the sick and the indigent of every sort and also for infirm people who need dressings and other medicines, as well as for abandoned orphans, travelling pilgrims and those in need”. The purpose of this foundation was to strengthen the Catholic hold on the population during the Counterreformation by offering social services. To make his foundation equal to this task, Prince-Bishop Julius Echter von Mespelbrunn had an infirmary built and gave this endowment rich sources of income: farms, forests and vineyards in the best positions. This foundation has survived the centuries and today its foundation capital has grown to 72 million Euros (56 million GBP / 107 million USD).

In Protestant principalities the church also tried to help the needy through alms boxes and parish funds for the poor. However, apart from that, the Protestant church saw itself as part of an authority established by an Almighty God and preferred to address poverty through workhouses and gaols.

After the war of liberation from Napoleon (1812-1814) Germany found itself confronted with what was delicately called the “social question”. This meant hunger and poverty, catastrophic working conditions and the beginning of the workers’ movement. Many different factors, such as freeing the serfs, abolishing the guild rules for different social classes, economic crises, urbanisation and the increasing industrialisation, had combined to leave masses of poor people without any kind of social safety net. The state, the established churches and the well-off were at first indifferent and then profoundly shocked by the social-democratic workers’ movement and its criticism of the bourgeois state and the churches that supported it.

Divine-right princelings blame the “Devil Drink”

The Protestant response to this social situation was the Inner Mission which combined charity with evangelising — not in foreign lands, but at home in Germany. This was the work of founders and promoters like Johann Hinrich Wichern (1808-1881) and Adolf Stöcker (1835-1909) who combined Pietism and Conservatism and, as part of the reaction against the Europe-wide revolutions of 1848, were favoured by the state.

These pastors and theologians were of the opinion that widespread poverty hunger and misery were the result of the proletariat turning away from the message of the Christian church. To prevent further punishment by an angry God, the masses must again be transformed into believing Christians. Then the widespread misery would disappear. This was in the tradition of Luther who saw the drunkenness of the poor, not as an attempt to forget their own misery, but rather as possession by the “Devil Drink”.

However, according to the 19th-century reformers, this was not the fault of the individual: “It is imperative that the godless be reached once more through the Word of God, which the church has so far been guilty of neglecting”. Those who were deeply disturbed by the religious and social need considered the existing church, due to its deadening formalism and its bureaucracy, to be a lost cause.

Smoking a hookah, (the height of fashion around 1900), the pastor tells them:

"We are not able to help you financially: we don't have the means.

But go faithfully to church, and there you will learn

how to bear hunger and misery with patience."

According to Wichern and his colleagues, the church must therefore repent and adopt the work of the Inner Mission. It should help the Inner Mission with money and personnel. However, the church authorities of the time had no intention of making any such commitment.

In 1833 Johann Hinrich Wichern gathered children and young people in his first “rescue home”: this was followed by hostels for migrant workers. These set “a signal against the proletarisation of society — and against the indifference of the established (state) church”. The Inner Mission founded by Wichern and others and the establishment of Deaconries (Diakonen) by Fliedner pursued three aims at once:

- to convince the church to accept that, in addition to preaching the Gospel, social work was also a part of its mission to world (Volksmission),

- to oppose the social-democratic workers’ movement which at that time regarded religion as a private matter and also took a political position against the alliance of throne and altar, which had resulted in established (state) churches,

- and to fight the Liberal idea of separation of church and state, which was seen as threatening the existence of the church and even of religion itself.

In 1848 Johann Hinrich Wichern and others founded the Inner Mission. The war against unbelief, poverty and social misery was lauded by Bodelschwingh in about 1900 as the “General Staff of the Army of Love”. The Inner Mission remained separate from the church, and therefore was also independent of the state. Finally, in 1996, it was recognised (under the name, Diakonat) as a special department within the Protestant Church of Germany (Evangelische Kirche Deutschlands/EKD).

At the end of WWII in 1945 Eugen Gerstenmaier had founded the Social Service Agency of Protestant Church in Germany (Hilfswerk der EKD), as a competitor to the official Protestant Church and the Inner Mission, to distribute American relief supplies in Germany. When this work ended, the two organisations merged in 1957 to become agencies of the Protestant churches in the various German states. Then in 1975 the Diakonisches Werk of the Protestant Church in Germany became a registered association in order to serve as an umbrella organisation. In the new millenium there are strongly differing views as to what the Diakonisches Werk's activities should be and how much independence its member associations should have.

Learning from the opposition

The Catholic Caritas Association wasn't begun as a revivalist movement like the Protestant Diakonisches Werk. Instead, it came about to gather the already existing Catholic associations, which were mostly sponsored by laymen, under one roof in order to more effectively coordinate the social and political work of German Catholicism.

However, this undertaking was not favourably viewed by the other Catholic associations that feared for their own influence, or by the Church itself, that didn’t want any central association above the control of the regional bishops. Due to resistance from both groups the formation of an umbrella organisation was prevented for many years. […]

Like the Protestant Inner Mission, the Caritas Association had historical antecedents. These included not only the long tradition of caring for the sick since mediaeval times, but also associations dating from the 19th century. Today the best known of these are Kolping’s Journeymen’s Unions (Gesellenvereine). At the time, however, these associations had limited influence.

Of more importance was W. E. Ketteler (1811-1877), who developed political ideas to try to solve the “social question”. He avoided romantic appeals for more Christian charity and called instead for state intervention and targeted social measures. His concepts formed the basis of both the “Catholic social teaching” and the social programme of the Catholic Centre Party (Zentrum). This is one reason why the Catholic Church sees no problem with public funding of the “Christian charity of the Church”.

Since the 1860’s the “social question” had been debated at the yearly Catholic Days. In 1880 the organisation Worker’s Welfare (Arbeiterwohl) was founded and in 1890 there followed the People’s Association for Catholic Germany (Volksverein für das katholische Deutschland) as

Since the 1860’s the “social question” had been debated at the yearly Catholic Days. In 1880 the organisation Worker’s Welfare (Arbeiterwohl) was founded and in 1890 there followed the People’s Association for Catholic Germany (Volksverein für das katholische Deutschland) as

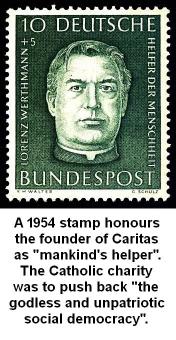

an attempt to no longer fight capitalism itself, but rather its outgrowths, in order to solve the social question and, at the same time, to push back the “godless and unpatriotic social democracy whose rapid growth — as is rightly recognised — profits primarily from these social tensions.

The end of Bismark's Kulturkampf (1870-1886) and the publication in 1891 of the first encyclical concerning social policy, Pope Leo XIII’s Rerum Novarum, set the stage for a Catholic counterpart of the Protestant Inner Mission.

In 1895 the priest, Lorenz Werthmann founded the first Caritas Committee in Freiburg and two years later became president of the Caritas Association for Catholic Germany founded in Cologne. Referring to the Inner Mission which was fostered by the Prussian State, he asked:

Why should we organise? Let us finally learn from our opponents. They have long recognised the usefulness of an organisation. […] Don’t we realise that on all sides Protestant groups, associations and cooperatives are operating with large financial resources and great ability under the special protection of the powerful of this world, to slowly and steadily make their mark in the field of charity and conquer the territory?

However, it wasn't until 1916, when the Caritas Association allowed itself to become decentralised and placed under the diocesan control that it was recognised by the German Conference of Bishops. It became the umbrella organisation of the local Caritas Associations in each diocese. Embedding Caritas in the Catholic hierarchy and making it a part of the Church gave it the protection of article 31 of the Reichskonkordat.

German taxpayers subsidise over 90% of faith-based social services

German taxpayers subsidise over 90% of faith-based social services