Roger Williams erects a wall between church and state

Roger Williams erects a wall between church and state

In the 1630s, when most of Europe was convulsed by religious wars, Roger Williams decided that this needed to be stopped. He introduced — and put into practice — the powerful new idea that there should be a wall between church and state. In his colony in Rhode Island he erected a "wall" to protect "God's garden" (the church) from the impure world and, at the same time, to give religious freedom to all.

Roger Williams was one of those remarkable people who are ready to give to others the freedom that they themselves have been denied. Like the other Puritans in the Colony of Massachusetts he had been obliged to leave England for opposing the state church. But unlike them he refused to turn around and do the same to others. The Massachusetts Puritans were quite prepared to force their own religious practices on everyone in their colony, including compulsory church attendance. Anyone who disagreed with this had to go.

English Puritans rejected the monopoly of the Anglican Church, yet once they came to power the Reformers made their religion compulsory. When the leader of the Massachusetts colony, John Cotton, was reproached for the Puritans' tendency to religious persecution so soon after fleeing England from persecution themselves, he was unrepentant. What the Puritans had fled from was “men's inventions, to which we else should have been compelled; we compel none to men's inventions”. What we compel to is “God's institutions”. [1]

Like almost everyone else in the 17th century, the Massachusetts Puritans still accepted the traditional Church doctrine that “error has no rights”. Not until the Enlightenment in the next century was this replaced by the notion that religious freedom was a human right.

The wall between chruch and state, Roger Williams' new idea

Roger Williams had fled England in 1630 to avoid coming under the Anglican Church, but he soon separated himself from the Puritan church of his new home in the colonies, as well. He found himself at odds with the government of Massachusetts when he asserted that the Colony had no right to steal the Indians’ land, even if they were pagans, that it shouldn’t deny the vote to the “unsaved” and that the state had no business prosecuting people for purely religious infractions. In fact, said Williams, “The civil magistrate's power extends only to the bodies and goods, and outward state of men.” [2] Roger Williams was the first to speak of the “wall of separation” between church and state.

In 1635 he was accused of holding "dangerous opinions against the authority of magistrates" and formally banished from Massachusetts. Once more Williams was told “my way or the highway”, and he was determined never to do this to others. The next year he purchased land from the Narragansett tribe to found a haven for dissenters. His Colony of Rhode Island welcomed those who faced persecution elsewhere, like Jews, Quakers and Deists.

Yet although he had created a haven in the American woods where no one faced religious persecution, for Roger Williams this was not reason enough and he tried to justify secularism in religious terms. He was influenced by the Seekers, a movement that gave rise to the Quakers, and like them he was metaphysically modest and didn't claim to have any monopoly on religious truth. Seekers respected all religions, but accepted none as authoritative. Instead they sought the truth “at source”. The Seekers held meetings, rather than religious services, where they waited in silence for the Lord to reveal Himself to them. [3]

To be able to freely seek the true religion, whatever it might turn out to be, Williams realised the necessity of separating church and state. He wanted to create a “wall of separation between the garden of the church and the wilderness of the world.” [4]

His image of the wall goes back to the ancient idea of a paradise garden, a sacred area protected from the world. Williams' concern was to protect religion from state interference and that included state sponsorship, as well. He opposed the idea of a state church, which was the norm in Europe at that time.

Williams felt that government is the natural way provided by God to cope with the corrupt nature of man. But since government could not be trusted to know which religion is true, he considered the best hope for true religion the protection of the freedom of all religion, along with non-religion, from the state. [5]

Like other Reformers of the 17th century, he felt that humans were owned by God and only had duties to their Creator. The concept of rights, which was needed to give his secularism wider appeal, barely existed. It wasn't until the Enlightenment that the idea of religious freedom was shifted from heaven to earth. That's when religious freedom came to be seen as a human right.

How did he do it? Three lessons came together.

Roger Williams' unusual background allowed him to reach conclusions that were far ahead of his time. His life taught him three things and when he drew the consequences, a powerful new idea was born: that there should be a wall between church and state.

1. The fires of Smithfield

Roger Williams was born about 1603, the year that Queen Elizabeth I died, and grew up in London on the northwest fringes of the city. The Williams family lived beside the open area called Smithfield, near the sheep-pen section on its western edge, of in this large field markets were held. The sheep pens in front of the Williams' house can still be seen in a picture of Smithfield Market painted two centuries later. [6] Smithfield was also where fairs were held, and there were other festivities as well — such as the burning of religious heretics.

Roger Williams was about eight years old when the last person ever burned in London for his religious opinions met his death at Smithfield. The doomed heretic, Bartholomew Legate, was a preacher for the Seekers, forerunners of the Quakers. They sought religious truth on their own and did not feel compelled to accept any dogma simply because some church said it was true.

This was a dangerous position to take. The Church of England court tried Bartholomew Legate on charges of heresy and then handed him over to the state to carry out the death sentence. (Clerics, of course, never stained their hands with blood.) On the orders of the new king, James I, this Seeker was burned to death right in front of the Williams home. This was a lesson on how church and state could collude to deliver a brave man to a horrible death. As Roger Williams wrote later, from that time onwards, he, too, adopted the position of the Seekers who refused to bow to the state church and insisted on trying to find their own way. [7] From a young age his goal became “a Libertie of searching after Gods most holy mind and pleasure.” [8]

2. The need (for Salvation) to avoid "corruption" of religion

Another strand in the thought of Roger Williams was what was known as “Separatism”. This was a logical extension of the Protestant Reformation. Like other Protestants, the Anglicans of the English Church had broken away from the Catholic Church which they felt had become corrupted and no longer represented the "pure" form of the early church. Soon the Puritans, in turn, broke away from the Church of England, to “purify” it, in turn.

However, tampering with a state church was a highly political thing to attempt. It seemed more prudent to conduct this religious experiment overseas, and a group of Puritans managed to get a charter from King Charles I to found the Colony of Massachusetts a good safe distance away. This allowed them to separate from the English Church in all but name. In the New World they were under no bishop and each congregation ran its own affairs. They had to be quiet about it, of course, since the Church of England was increasingly hostile to Puritanism and what King Charles had given, he could also take away. [9] The last thing the Colony of Massachusetts needed was an open separatist like Roger Williams who advocated a public break with the Church of England.

However, tampering with a state church was a highly political thing to attempt. It seemed more prudent to conduct this religious experiment overseas, and a group of Puritans managed to get a charter from King Charles I to found the Colony of Massachusetts a good safe distance away. This allowed them to separate from the English Church in all but name. In the New World they were under no bishop and each congregation ran its own affairs. They had to be quiet about it, of course, since the Church of England was increasingly hostile to Puritanism and what King Charles had given, he could also take away. [9] The last thing the Colony of Massachusetts needed was an open separatist like Roger Williams who advocated a public break with the Church of England.

Soon the Massachusetts authorities encountered further problems with the young Puritan preacher. Not content to challenge the legitimacy of the English Church, he even began to question the purity of the Puritan one and finally decided that he must separate from that, as well.

The impulse of separation was a natural extension of the perception of spiritual stain and impurity, and Puritans saw stain everywhere. Central to Puritan ecclesiology was the line of demarcation between the godly and ungodly, the holy and the profane. [10]

In the 17th century this drive to avoid spiritual impurity led to a series of further separations, as churches separated from the churches which had themselves separated from Rome. However, one of the remarkable things about Roger Williams is that unlike others, he did not set himself up as the leader of some new and purer church — even though his status as the founder of a new colony would have let him assume that role, like so many others. Instead, he remained true to his Seeker beliefs, unwilling to impose some new orthodoxy, even in the name of spiritual purity. Thus he didn't separate in order to found a new church, but in order to keep any church from impeding people's earnest search to learn God's will.

3. A lesson from the Indians

Yet without a third crucial experience Williams could not likely have made the bold leap and founded a colony where everyone enjoyed complete religious freedom. In the 17th century it was assumed that a common religion was necessary to ensure social peace. This was the lesson that Europe had drawn from that century's devastating religious wars. Furthermore, to ensure the authority of the state, this common religion should be a state church, in other words, all subjects must follow the religion of their rulers. Otherwise, it was feared, they might try to topple the king and install a ruler of their own faith. This had indeed been attempted when Roger Williams was a baby: the Gunpowder Plot was an attempt to bring back a Catholic king. This plot, though foiled, inspired religious oppression of Catholics and created a vicious circle of suspicion and disaffection that was only ended by the Catholic Emancipation Act in 1829.

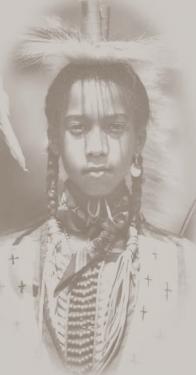

However, Roger Williams knew that this tragic cycle of exclusion was totally unnecessary. People didn't need a common church — or even any church at all — to live in harmony with their neighbours. He had experienced something that his contemporaries believed to be impossible, for he had lived among the Indians of Rhode Island, the Narrangasett, and even written a book about their language. He knew at first hand that people could tell the truth without swearing on the Bible, could help their fellows without any religious duty to do so and could keep the peace without oaths of allegiance to a divinely-appointed ruler.

However, Roger Williams knew that this tragic cycle of exclusion was totally unnecessary. People didn't need a common church — or even any church at all — to live in harmony with their neighbours. He had experienced something that his contemporaries believed to be impossible, for he had lived among the Indians of Rhode Island, the Narrangasett, and even written a book about their language. He knew at first hand that people could tell the truth without swearing on the Bible, could help their fellows without any religious duty to do so and could keep the peace without oaths of allegiance to a divinely-appointed ruler.

Roger Williams had gone among the Indians to teach them Christianity but, true to his Seeker beliefs, he had remained open-minded. He let the Indians teach him a lesson that he could learn nowhere else: that church and state need not be linked.

He gives three reasons for this. He recoiled from the prospect of an insincere profession of faith made due to fear or expediency: “Forced worship stinks in God’s nostrils.” He also warned of the worldly influence on the church through state sponsorship, which made it “national” and “ceremonial.” And finally, alluding to the “flames about religion” which he had witnessed in England, he affirms that “there is no prudent Christian way of preserving peace in the world but by permission of differing consciences.” [11]

When Roger Williams was exiled from Massachusetts in 1636 he and a few companions founded a little settlement. There church and state were completely separate and they underlined their religious motives for doing this by naming it “Providence”. It was a small settlement overlooking the tidal Providence River. On the river bank they built their timber-framed cottages, the wattle-and-daub walls protected from the rain by the deep eaves of thatched roofs. Behind the cottages, in a field which rose to the foot of the bluffs, they planted multicoloured Indian corn.

Life in the new settlement proved a struggle. In fact, the next year, when the Governor of Massachusetts paid a visit to the impetuous young preacher, he was touched by their poverty and quietly pressed a gold piece into Mrs. Williams' hand. The hamlet was small, mosquito-infested, pig-ridden, dirt-laned, isolated, insecure and poor. Yet at that time it was perhaps the freest place on earth. [12]

Continuing the tradition of Roger Williams

For a lone British Quaker's defence of church-state separation and religious freedom, see Iain McLean's “Open letter to the Bishop of Winchester”, 5 February 2010. This brilliant piece shows some of the damage done by allowing 26 unelected Church-of-England bishops to sit in the British Upper House of Parliament.

Quakers are not the only Dissenters sometimes persecuted by the state church in England. Baptists also became targets, and even today some of them maintain their proud tradition of advocating the separation of church and state. Thus in 2013 the American Baptist minister and politician Mike Huckabee said, “It's time for churches to reject tax exempt status completely; freedom is more important than government financial favours.” [13]

The legacy of Roger Williams in US constitutional law:

The “wall of separation”... has been one of the two most enduring metaphors in constitutional interpretation. (The other is the “marketplace of ideas.”) Protestant justices were originally drawn to the wall, and subsequent Protestants have reached the separationist results that it demands. Catholics, for the most part, reject the idea of a wall of separation and (along with some Evangelical Protestants) support what they call non-preferentialism, whereby government is forbidden only in preferring one religion over another. [13]

Roger Williams' writing online:

♦ “Roger Williams (theologian)”. [Excerpts from many of his books, quotes by and about him and a good bibliography] http://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Roger_Williams

♦ Roger Williams, The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution (1644). [Excerpts]

http://www.swarthmore.edu/SocSci/bdorsey1/41docs/31-wil.html

Notes

* Photograph reproduced by kind permission of the Library of the Religious Society of Friends in Britain. The Quaker bottle of port is housed in a handsome wooden case. The label reads:

This bottle of Port Wine was given by John Gurney Bevan to John Brown, John King and John Brown, jnr., when imprisoned in the Fleet in London in the year 1797, under an Exchequer process for the non-payment of Tithes at Haddenham, and at the request of John Brown, jnr. is not to be opened until the Church of England is severed from the State by Legislature.

Presented to the Library by John Brown of Wisbech, in 1898

Unfortunately, modern British Quakers seem to have turned their backs on their own tradition of secularism. They have joined a national council of churches which lobbies for faith-based social services. Thus they endorsed the Churches Together 2010 guide for voters which warns that “some politicians” are “against religious values and motivation being expressed in politics”, even though no one is proposing such a thing. This scare tactic serves to mask the real issues about granting political power to unelected clerics and giving to religious organisations public funds, opportunities to proselytise and the legal right to discriminate.

1. Sanford H. Cobb, The Rise of Religious Liberty in America: A History, 1902, p. 69. http://www.archive.org/stream/riseofreligiou00cobb/riseofreligiou00cobb_djvu.txt

2. Roger Williams, The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution (1644). http://www.swarthmore.edu/SocSci/bdorsey1/41docs/31-wil.html

3. “English Dissenters: Seekers”, Ex libris. http://www.exlibris.org/nonconform/engdis/seekers.html

4. Williams in a 1644 response to the theocratic Puritan clergyman John Cotton, quoted in John M. Barry, “God, Government and Roger Williams’ Big Idea”, Smithsonian Magazine, January 2012. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/god-government-and-roger-williams-big-idea-6291280/

5. Cyclone Covey, The Gentle Radical: Roger Williams. New York: The MacMillian Co., 1966, cover leaf. Cited at: http://users.erols.com/igoddard/roger.htm

6. Smithfield Market, watercolour on paper by Thomas Rowlandson, 1810; in the Guildhall Library, City of London

7. Ibid., p. 3.

8. Ibid., p. xi. Google reprint

9. Timothy L. Hall, Separating Church and State: Roger Williams and religious liberty, (University of Illinois Press, 1997), p. 24.

10. Ibid., p. 23.

11. Roger Williams, “Letter to Major John Wilson and [Connecticut] Governor Thomas Prence”, Providence, 22 June 1670. http://www.worldpolicy.newschool.edu/globalrights/religion/Williams-forcedworship.html

12. Covey, p. 134.

13. “Mike Huckabee says churches should give up tax exempt status”, Examiner, 11 June 2013.

http://www.examiner.com/article/mike-huckabee-says-churches-should-give-up-tax-exempt-status

14. Scot Powe, “Robes and Vestments”, (review of Donald L. Drakeman, Church, State and Original Intent), New Republic, 13 April 2010. http://www.tnr.com/book/review/robes-and-vestments