How secrecy shielded the Legion of Christ from the law

How secrecy shielded the Legion of Christ from the law

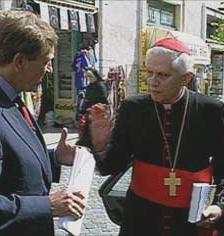

The secrecy vow removes Legion of Christ members from the protection of secular law. The Vatican did not intervene, despite more than 50 years of warnings about its founder Fr. Marcial Maciel (1920-2008). The Legion is too useful, because it goes “where the priest can’t”, bringing money, influence and new priests. Cardinal Ratzinger was shown on ABC TV in 2002 refusing to discuss the scandal. Yet the Vatican claimed in 2010 that even the priests in the Legion didn’t know what was going on....

Benedict XVI said that it is a mistake when the Church “adapts herself to the standards of the world”. Her future lies, instead in the cultivation of a “creativc minority”, forming an uncompromisingly conservative core consisting of “small communities of believers...whose enthusiasm spreads”. To try to bring this about he supported conservative groups that have been accused of being cult-like, such as the Society of St. Pius X, Neocatechumenal Way, Opus Dei, Order of Malta and Legion of Christ. [1]

In 2002 ABC television showed an attempted interview with Cardinal Ratzinger, later Pope Benedict XVI, about the Legion of Christ. When the journalist started to ask awkward questions about its founder, Father Marcial Maciel, Ratzinger tells him the time is not right and slaps his hand. The news story and TV clip are from 26 April 2002. [2] The same incident also appears in this trailer (at the bottom of the page) for the award-winning documentary, “Vows of silence”.

In 2002 ABC television showed an attempted interview with Cardinal Ratzinger, later Pope Benedict XVI, about the Legion of Christ. When the journalist started to ask awkward questions about its founder, Father Marcial Maciel, Ratzinger tells him the time is not right and slaps his hand. The news story and TV clip are from 26 April 2002. [2] The same incident also appears in this trailer (at the bottom of the page) for the award-winning documentary, “Vows of silence”.

A month after Benedict XVI became pope in 2005 the Vatican investigation of Maciel was dropped without explanation [3] The following year, after he had become an embarassment, Maciel was finally retired. It wasn’t until 2010, under public pressure due to the priestly abuse scandal, that the Vatican even had a report prepared on the Legion of Christ. Its contents are being kept secret and the extremely useful Legion is not being disbanded. [4]

Churches can get exemption from the law by swearing people to secrecy so that crimes are not reported either by the criminal's superiors or by his victims. Sometimes this oath of secrecy is applied after the fact, as with many victims of abuse by diocesan priests. However, in the Legion of Christ all members take a vow of secrecy upon entering, so that no damaging information of any kind can come out.

On the wider issue of Cardinal Ratzinger keeping the abuse cases secret, see “Church Office Failed to Act on Abuse Scandal”, New York Times, 1 July 2010, “Catholics, it’s you this Pope has abused”, Independent, 9 September 2010 and “Truth To Power”, The Atlantic, 18 March 2010. This last is a short, hard-hitting statement by the great Catholic theologian, Hans Kung.

A first line of defence to shield the Pope would be, of course, be to claim that even the prelates in the Legion of Christ had no idea that abuse was going on and this is exactlywhat the papal investigator maintained. Oh yes, he admitted, they had heard of “denunciations published in the newspapers. [...] But it is something else to have proof that they were founded and even more that they were certain. This came only much later, and gradually.” [5]

There are, of course, advantages to not knowing, or at least keeping wealthy donors from knowing. One lawsuit charges that a benefactor was “led to believe Maciel was a saint, even as Legion officials knew about serious allegations against him”. Another alleges undue pressure by the Legion in order to get a bequest of $60 million. [6]

How secrecy shielded the Legion of Christ from the law

Excerpts from

Les nouveaux soldats du Pape. Légion du Christ, Opus Dei, traditionnalistes

(The new soldiers of the pope: Legion of Christ, Opus Dei, the traditionalists)

Caroline Fourest and Fiammetta Venner

The Legionaries of Christ began in Mexico with a group of ten youths in 1941. This makes it newer and less well known than Opus Dei which was founded in Spain in 1928. However, like Opus Dei, the Legionaries of Christ have also been widely claimed to act like a sect. The Legion's unconditional loyalty to the pope, its recruitment of new priests and its successful fundraising all serve to bolster its power within the Church, whilst its network of schools and circles of influence enables it to be active in almost every social sphere: the economy, education and communication.

In a few years, thanks to organisation and a iron discipline, the Legion has succeeded in establishing itself as one of the incontrovertibly armed branches of the Vatican. The Church now openly relies on its soldiers to spread its message. Zenit, the press agency of the Vatican, is entirely in the hands of the Legionaries of Christ, which makes them into the official spokesmen of the Holy See. This is a symbol of the real trust on the part of Rome and of the true fidelity on the part of the Legionaries. Marcial Maciel, the founder of the Legion, [who was born in 1920] died on 1 February 2008. Until his death he never ceased repeating to his followers: “We march to the rhythm of the Church, neither one step in front, nor one step behind.” [7] [pp. 21-22]

Apart from its Spartan and sect-like methods, the Legion of Christ is unfortunately known for hushing up the many cases of sexual abuse within it. None of which prevents the Church from encouraging young people to get involved with it. Nor does it keep the Church itself from counting on it to evangelise, notably in Latin America, where the Legion allows it to fight the influence of the Protestant “sects”. [p. 22]

1941: Maciel forms a small group in Mexico

Although Maciel was expelled from three seminaries, he was protected by his family which included several bishops. His pattern of seeking out powerful protectors was to serve him well, both in fulfilling his ambitions and in granting him impunity from the charges levelled against him.

He held tenaciously to his goal of starting his own “congregation”, a type of religious order, (which at first he intended to call the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart). At the age of 21 he gathered a group of ten boys who wanted to become priests and rented a house to serve as his first seminary.

1946: Maciel’s rise to power, despite warnings from the start

In 1946, at the age of 26, he went to Rome to begin the long process of getting official recognition for his congregation. There he obtained the necessary nihil obstat from the Vatican. This means that “nothing stands in the way” of a bishop establishing it as an “institute of consecrated life of diocesan right”. (Canon 579: Diocesan bishops, each in his own territory, can erect institutes of consecrated life by formal decree, provided that the Apostolic See has been consulted.) The stage after that is to get the congregation recognised by the pope as an “institute of consecrated life of pontifical right”. (Canon 589: An institute of consecrated life is said to be of pontifical right if the Apostolic See has erected it or approved it through a formal decree.) And the final step is to have it confirmed. However, that was still far in the future.

In 1946 he achieved the first official step and, perhaps even more important, succeeded in making the right connections in Rome. When Pius XII asked Cardinal Montini to help Maciel, he handed the young priest over to a powerful patron.

The first alarm about Maciel’s plans for a congregation appears to have been sounded that same year. At the Pontifical University of Comillas in Spain, where the first of Maciel’s seminarians were taking courses, it was clear that these “new gladiators of the Vatican”, with their uniforms, strict piety and rigorous sports, were obsessed by the military. Even at this stage their leader came under critical scrutiny.

An important official of that university, a Jesuit, took the trouble to write to the Holy See to express his concerns about the methods and the inexperience of the founder of the Legionaries. The warning was serious enough to set back its validation as a congregation. According to former Legionaries who knew that era, when Marcial Maciel was away, the seminarians used the opportunity to confess about sexual assaults. [pp. 32-33]

These confessions were in addition to others received by the Jesuits in Mexico. Thus [from the very beginning], when Maciel was trying to obtain the canonical establishment of his community, the founder was strongly suspect. Rome even appointed an assessor to follow the development of the congregation, Father Lucio Rodrigo. He sounded the alarm. On the basis of testimony of seminarians who said they had been raped and abused, he vigorously denounced Maciel’s habitual lying, as well as the unacceptable moral pressure [on his seminarians]. Thanks to numerous connections that he enjoyed in Mexico, Maciel still managed to get signed the document definitively consecrating the Congregation of the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart [under “diocesan right”] just before the arrival of the letter of Lucio Rodrigo… And as it is very hard to undo a consecrated congregation, Maciel continued his path in spite of the mistrust. [p. 33]

1956: Vatican again alerted, this time by the Mexican church

On 30 September 1956, on returning from a trip to Spain with his seminarians, Father Maciel was informed that he had been relieved of his duties for the young people of his congregation. He could remain the director general but an enquiry was underway and a curate had been appointed to administer in his stead. A letter from Mexico had alerted the Vatican. Signed by several notables in the Mexican Church, it reiterated the doubts about the man whom it accused of imposing moral pressure of the young people and of drugging them. Once again, the hagiography of Maciel is strangely silent about the details of these accusations. It’s impossible to know if the suspicions of sexual assaults, confirmed years later, were already present or if they were only suggested in very vague terms. [p. 34]

One thing is clear, the doubts were sufficiently serious that the notables of the Mexican Church, even though this was where Maciel had support, recommended sending him to a psychiatric hospital to “detoxify his organism”. This last recommendation was an allusion to the anti-depression drugs that Maciel required his disciples to inject him with almost daily. In fragile health, in particular because of his stomach, the founder several times believed himself to be dying of fatigue and physical misery. Years later it would come out that he also used this excuse to explain to the young seminarians that the pope had relieved him of the duty of chastity… and to demand that they masturbate him on the pretext of relieving his misery. [pp. 34-35]

1965: Papal seal of approval and permission to work with young people

Despite all the warnings about Maciel from various quarters, two years after the Vatican’s inquiry began it came to nothing. This was thanks to the support of Cardinal Montini, soon to be Pope Paul VI. Furthermore, in 1965 the Legionaries were even granted the decretum laudis. This Vatican seal of approval meant that the congregation was approved by the pope as an “institute of consecrated life of pontifical right” and had achieved a further step on the road to final recognition.

Not only had the congregation not reviewed and corrected its method of training the seminarians, but it applied it henceforth to young lay people through its branch, Regnum Christi – the Kingdom of Christ – founded in 1965. Under the influence of the debates concluding the Council of Vatican II, Father Maciel understood that he no longer needed to content himself with forming saintly priests: he could also extend the kingdom of Christ by evangelising in the very centre of society, through education and the family. That was the real aim of the lay branch. According to Ganzague Monzon [a priest in the Legionaries], it is charged with “transmitting the Gospel where the priest can’t go”. [8] Present in many dioceses, this lay movement develops missions in perfect “collaboration with the bishops”. [p. 36]

Maciel had to wait until 25 November 2004 for the Holy See to promulgate the definitive decree of approbation of the statutes of the movement “Regnum Christi”, essentially because of the difficulties in terms of Canon Law that are faced by any lay movement. The few movements chosen are those which know how to make themselves indispensible, especially for recruiting young people under the banner of Christ, such as Opus Dei or the Legionaries of Christ. [pp. 36-37]

Education is the principal mode of action of the Legionaries who run close to 200 educational institutions spread over 25 countries of the world: universities, schools and centres of specialisation. [p. 37]

The Legionaries go into parishes to recruit young people, often through the programme called “Education, Culture and Sport” (known as ECYD according to its initials in Spanish).

A former member remembers the orders given to the Legionaries sent to the parishes to recruit: “Your mission is to recruit three students in each class for the ECYD programme. Play basketball with them, lead them to sign into the programmes. The goal is recruitment.” [9] This is how the whole of education, is seen by the Legionaries. [p. 39]

The next step is to separate the future Legionaries from their families.

With a view to recruitment, the movement must persuade parents to entrust their children to summer camps or courses abroad, often under the pretext of leaning English in Dublin or in the United States. Such an apprenticeship is quickly transformed by putting these children under the guardianship of directors of conscience, the team leaders whose task it is to lead them towards a seminary. To make them more docile, these leaders have no hesitation about using auto-suggestion: a timed programme, with sleep reduced as much as possible (from 10:30 pm to 4:30 am), and a full schedule where each minute is taken up by a direct order or one dictated in a book. The pupils are obliged to memorise the 368 verses of the red book which is to guide them for each second of their life. [pp. 40-41]

When they are minors, the young people entrusted to the schools of the legionaries only have the right to write to their families once a month and must avoid all direct contact until the end of their training, with the exception of Christmas. Even as adults, the only have limited access to those close to them: their correspondence is inspected and their telephone conversations are overheard. For the legionaries, as a former member sums it up, “the world is divided into two camps, the Legionaries and the profane (which includes family, friends or those of other religions). Relations with the profane must be limited in the interest of the Legion”. Seminarians are also requested to limit their contacts with the outside. “Our religious may reply to letters which they receive, on condition that it isn’t a matter of a regular exchange which would makes them lose time that they should be devoting to their apostolic mission” states the constitution of the Legion. [10] [p. 41]

To draw the young people in, the Legionaries often conceal the nature of the programme, leading them to believe that they’re taking a trip to learn a foreign language. However, even when they discover that they have been tricked, they often feel flattered to be counted among the élite of the youth for Christ. A further surprise can come if a youngster tries to leave.

This isolation of the young people from their families helped Maciel practice sexual abuse.

According to the rule established by Marcial Maciel, the Legionaries take a private vow to never come before the courts, act as a witness or even criticise another Legionary: “I promise and wish never to criticise the acts and decisions of my superior and to inform him if I know someone who has broken that promise.” [p. 47]

This rule materially delayed the accusations against him of abusing nine boys… the only ones who dared to break the [vow of] silence. Their versions agreed and reinforced one another. They shed new light on certain omissions in the hagiography of Marcial Maciel, regularly expelled from seminaries or accused by other priests after hearing the confessions of his seminarians. Above all they allow a better understanding the aim of certain rules dictated by the founder: not to mix, the need to cut of the young people from their attachments and their families, the personality cult, the ban on denouncing another legionary and finally the strict control of their speech in public…. Everything is in place to facilitate the abuse of the young people lost in admiration for Marcial Maciel, and traumatised at the very idea of displeasing him. [pp. 47-48]

1978: Ex-Legionaries and bishop appeal to Vatican, but no response

Juan Vaca, a young Mexican who had been in the congregation since he was ten years old, was abused by Maciel for many years. In 1976 he finally left the Legionaries (and is now a psychology professor in New York).

Liberated from his vow, he wrote to Rome to recount the subterfuges at the centre of the Legion and to call for the dismissal of Father Maciel. This was in October 1978. Already for two years two other priests, victims of the same abuse in the course of their seminary [studies] in Rome and in Spain between 1940 and 1950, had warned the hierarchy. They confided in Bishop John McGann, who sounded the alarm. The Holy See acknowledged receiving this, but did not react. [p. 51]

It had to wait till 2002 and the pressure of public opinion for the Church to abandon its denial concerning the rapes committed by its priests in the United States. According to a Church report, 4,392 priests in the United States raped 10,667 children between 1950 and 2002. [11] For their part the victims’ associations talk of almost 100,000 abused children of whom 80 percent don’t want to talk about it. [That it happened on] such a scale is explained by the “rotation” practised under John Paul II, and thus under Cardinal Ratzinger. When a family was about to report a rape committed by a priest to his superior, the bishops chose to make the family feel guilty in order to dissuade the parents from lodging a complaint, to deny the suffering of the child and to support the rapist priest and transfer him to another parish, often several kilometres away — at the risk of creating new victims. [12] Yet in view of his good and loyal services, Father Maciel risked even less than the lowly priests [who got quietly moved]. [pp. 51-52]

1946-2004: Support under five popes until the scandal becomes public

Under Paul VI, [whom Maciel had won as his patron in 1946 when Montini was still a cardinal] the founder of the Legionaries was untouchable. The era of John Paul II promised to be just as lenient. Obsessed by the battle against communism and the resistance against liberation theology in Latin America, the new pope desperately needed missionary movements such as the Legionaries of Christ. In January 1979, John Paul II made the first official trip of his pontificate to Mexico. Father Maciel accompanied him at every stage in his private plane. Impressed by the ability of Regnum Christi to mobilise for his visit, the Vicar of Rome naturally went back convinced that he depended on that energy to reconquer the continent.

As a public display of gratitude, the congregation and its founder were invited into the gardens of the Vatican City on 28 June 1979. According to Gonzague Monzon it was the beginning “of a long friendship” between John Paul II and the Legionaries. [13] On 3 January 1990 John Paul II celebrated the 50th anniversary of the foundation of the congregation with a symbolic gesture: he ordained 60 priests of the Legionaries of Christ in Saint Peter’s Basilica. In October of the same year the Pope invited Maciel to participate in the synod of bishops on the training of priests. That showed how much the education given by the Legionaries was appreciated. In 1994 several large Mexican papers published half a page glorifying the founder. He was pictured kissing the ring of the Pope under the title: “an efficacious guide for youth”. This compliment, taken from an open letter addressed by John Paul II to Marcial Maciel, rubbed salt into the wounds of his victims. [pp. 52-53]

Between 1978 and 1989 other former Legionaries alerted the Curia without receiving any reply. During this whole period the attitude of the Legion consisted of denying [it] or of talking of accusations coming from enemies who hoped to destroy the Legion. The congregation hardly ever responded to requests for interviews, including ours. [14] These interviews would have obliged them to explain their methods: “The Legionaries don’t wish any publicity” was the reply. The Vatican would have been able to force them to explain themselves, but it protects itself well from doing so. In the nineties, when seven old Legionaries were about to break their silence to denounce the sexual abuse practiced at the centre of the Legionaries, Father Maciel began to worry. At a beatification ceremony in 1992 he confided “Don’t begin the process of canonisation less than thirty years after my death”. [15] Did he mean when the victims of sexual abuse were all dead? [p. 53]

It took until March 1997 for Marcial Maciel, then 76 years of age, to deign to deny the accusations of rape made against him — half-heartedly. In a statement given to the American magazine Inside the Vatican he settled for stating: “It’s a matter of completely false accusations.” Exasperated by such a denial and such contempt, several of his victims wrote to the Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith — thus to Cardinal Ratzinger — to demand a canonical trial. In their letter the former Legionaries explained that Maciel used the confessional to “pardon” his victims “their” sins, during the course of the rapes that the confessor committed on them. The ambassador of the pope, charged with writing up the dossier, insisted on this point: “to profane the confessional was a crime”. In spite of a damning dossier, Cardinal Ratzinger chose to stop the instruction about the dossier without giving any explanation. [pp. 53-54]

Several months later, in 1998, John Paul II even increased the gestures of friendship toward the Legionaries. On the 19th of March he visited the Centre for Higher Studies of the community in Rome and talked with the seminarians. The same year the Legionaries and the Regnum Christi were invited to the large gathering of the new communities. Maciel’s victims despaired of ever seeing the Church come to their aid. Some of them chose to seek justice outside [the Church]. In 2002 the association REGAIN [Religious Groups Awareness Network] created to unite the testimony of former members of Regnum Christi, began to talk about it: “the members, present or past, and all those who seek justice and truth, healing, are urged to join us” said their website. [16] The Legion tried several times to get the site closed, but it remained accessible and the Holy See pretends not to know about it. [p. 54]

On 30 November 2004, when the scandal of the rapist priests had been staining the Church for two years, John Paul II received the founder of the Legionaries of Christ at Rome for the 60th anniversary of his priestly ordination, in the company of 4,000 Legionaries of Christ. Far from curbing their fervour, the reigning pope exhorted them to proclaim the Gospel with “fearless witness” and “to announce the truth about God, about man and about the world with courage and intellectual depth, pushing aside every form of fear which could paralyse” their actions…. Less than a month later, REGAIN produced a damning [piece of] new evidence. It was from a novice raped by a priest of the Legionaries:

I’ve been in the Legion for five years. I was recruited at the age of 13 years and became a novice at 16 years. (…) I was abused in 1995. I spoke of it in 2000 to my counsellor (…) No action on this was taken by the Legion. [My abuser] was heard and he denied it. I was asked how I could have invented such a story. (…) they treated me like a liar and [my abuser] was about to be named principal of a school of the Legionaries in Medellín. (…) They didn’t act until I complained to the police.

Until that point the abuser was protected by the Legion. [pp. 54-55]

A year later, the Curia finally decided to follow up on the complaints filed against Marcial Maciel. A permanent Promoter of Justice was charged with verifying whether the victims wished to follow the procedure. Hastily the Congregation elected a new member to head it, Alvaro Corcuera, to serve as a screen and preserve appearances. At 47 years of age, the rector of the Legion of Christ's Centre for Higher Studies in Rome had above all the advantage of not having been accused of rapes like the founder. For Maciel the sentence came in May 2006 and it was incredibly lenient. At that time 85 years of age, Rome was content to require him to “give up all public ministry and to lead a discreet life of prayer and penitence”. He was never [legally] pursued nor was [his priesthood] revoked. Although it was not a question of beatifying its founder, in October 2006 the pope chose instead to canonise his benefactor: the great-uncle of the founder, Bishop Rafäel Guizar Valencia. [pp. 55-56]

2007: Sleight-of-hand on vow of silence

With great fanfare Benedict XVI derogated the private vow of silence of the Legionaries of Christ which was used to protect them from any complaints. According to the congregation's constitution, all members vow “Never to criticize externally the acts of government or the person of any director or superior of the congregation by word, in writing or any other way. And if he knows for certain that a religious has broken this commitment, to inform the latter’s immediate superior.” However, the rule of silence was quietly replaced by a contract of confidentiality. In terms of public relations, however, this manoeuvre proved a great success, being hailed as “an opportunity to promote transparency”.

Beginning in October 2007 the Church took some measures. It considered that private vows not communicated to the curia are null and void. This allows in principle the removal of the rule of silence, proclaimed but not communicated, serving to protect for too long the abusers at the centre of the Legion. In fact, at the same period, the Legionaries received from their superiors a contract forbidding them to pass on information about possible sexual abuse. The suppressed rule of silence is now replaced by a contract of confidentiality which guarantees the maintenance of omertà. [This is the Mafia’s prohibition on cooperation with the police, even when one has been the victim of a crime.] As for the rest, until his death, Marcial Maciel spent his days happily with his disciples in Mexico. [p. 56]

The Legionaries have also been allowed to continue opening many “faith schools” as well as schools where poor children can learn technical trades. The opponents of the Legionaries have described the harshness of the education and the recruitment of young people, yet nothing has been done. However, thanks to the families of some of the children, since 16 November 2007 cases of sexual abuse have been reported. The mother in one family lodged a complaint against the Mano Amiga de Zomeyucan School. [Mano Amiga, Helping Hand, is a chain of Legion schools across Latin America. It also runs a recruitment programme under the guise of an “ecumenical, non-denominational Christian” volunteer organisation with no paid staff.] This was for rape and aggravated assault against her daughter. Father Ricardo had fondled her under the pretext that God had told him to. At the same time other complaints were aired in the media, like those of the Bonilla family whose three-year-old son, a pupil at the prestigious Colegio Oxford Preschool, showed signs of sexual abuse. All together nine parents reported sexual abuse to the investigating officers. [pp. 56-57]

All that doesn’t prevent the Church from letting the Legion continue to run schools, training centres and activities for young people all over the world. Several schools which were formerly run directly by the Catholic hierarchy have even been entrusted to them, like the Donnellan school, [now Holy Spirit Prep] ceded by the Archdiocese to the Legion in 1999. A short while after they took it over, the principal and three staff members were fired for “taking part in a mutiny”. One of them, a therapist, was sent to Rome for a coaching session with the Legionaries. The reason? He had refused to reveal to the priest the confidences of his patient, received during counselling. [p. 57]

In spite of the protests of parents against this lack of respect for professional confidentiality and against [professional] practice, the Catholic hierarchy chose to support the Legion. William Wiegand, Bishop of Sacramento, even asked the Legionaries to found a university in his area. [In 2007 his diocese went so far as to sue an alleged child abuse victim for coming forward after the expiry of the statute of limitations. The accused priest fled to Mexico.] As for the Archbishop of Atlanta, John Donoghue, he gave complete power to the Legion and Regnum Christi to teach catechism to the children of his diocese. Likewise for Cardinal Roger Mahoney who, in spite of warnings from various sources, entrusted several schools to the Legionaries. This was in 2004 when Archbishop Mahoney of Los Angeles already had almost 500 proceedings against the priests for sexual abuse. The Cardinal ignored them. It wasn't until July 2007 that he even offered public excuses to some of the abused. No one thought for a minute of dismissing the Legionaries of Christ from their educational mission. [pp. 57-58]

Legion is kept for recruitment and fundraising

It is too useful for combating liberation theology and the “sects” [Protestants].

When it comes to paedophilia in the heart of the Church, Joseph Ratzinger has shown himself more concerned than John Paul II about “cleaning the Augean stables”. But neither John Paul II nor Benedict XVI have thought for a minute of carrying the policy of precaution to the point of expelling the Legionaries of Christ from the Church, as was done with the traditionalists or the proponents of liberation theology. The Legion is too obliging and useful to consider dispensing with its services. [p. 58]

In a cartoon titled “Repentence” the Mexican satirist José Hernández has the Pope say: “Father Maciel is affecting what we hold most sacred — the finances of the Legionaries”.

Update: Since Maciel's public disgrace, the Legion's line has changed

There have been reports from ex-members that outside groups (e.g. other religious orders) are jealous and are out to get them and that evil “detractors” were willing to tell lies about their founder. Since the fall from grace in the winter of 2009, the party line has changed to “God is able to draw straight with crooked lines”; implying that Marcial Maciel had some faults but the religious order and movement that he founded were true to the faith. [17]

A belated “apostolic visitation” by a Vatican investigator was announced on 29 September 2010, for Regnum Christi. [18] This is the lay group founded by Maciel to recruit future members for the Legion of Christ, which means that is full of young people.

Despite the long-awaited expressions of Vatican concern, a priest who is a member of the Legion in Mexico complained to his superiors in a 27 July letter that photos of the disgraced founder remained on display and that the group's leaders were still “grooming” wealthy families in Mexico “then tapping into their money”. “This is a methodology that was institutionalised by the deceased founder, who lived a life without scruples,” he said. [19]

Perhaps it is to prevent this longterm and profitable practice from being disrupted that the Vatican is moving so slowly. The papal delegate overseeing the reform has said that the process may take “two or three years or even more”. The day after the investigator, Archbishop Velasio De Paolis, sent his letter to the Legionaries, he was named by the Pope to become a cardinal, which will lend him more authority. [20] Another qualification for dealing with this secretive money-making machine is that he also heads the Vatican's Prefecture for Economic Affairs. [21]

Update: leaked Vatican documents give further evidence of a coverup

In March 2012 Pope Benedict XVI made a trip to Mexico in what looked like a window of political opportunity. The last preparations for the Pope's visit coincided with an important vote in the Senate about whether to alter the Constitution in order to state that Mexico is to remain “secular” (laica). [22] And since the President iwas the only one to meet with the Pope, the visit was seen as a boost for the Vatican-friendly ruling party shortly before the important summer elections. [23]

Unfortunately for the Pontiff it also coincided with the publication of a damaging book. Called La voluntad de no saber (The wish not to know), it contained 212 leaked Vatican documents on Fr. Maciel whose long career of sexual abuse began in Mexico. The documents stretched back to 1944. The Rev. Richard Gill, a prominent U.S. Legion priest until he left the congregation in 2010 after 29 years, said the collection of documents “shows that there were solid grounds for the removal of Fr. Maciel more than 50 years ago.” And, of course, for 30 of those years it was Benedict XVI who was ultimately responsible for ensuring that priestly predators be removed, first while he head of the CDF and thereafter as the pope. [24] Three months after the revelations about Maciel, came another book of leaked Vatican documents, which also revealed the coverup of clerical abuse. This was His Holiness: The Secret Papers of Benedict XVI, whose ninth chapter revealed the existence of secret report to Benedict XVI on the Legionaries of Christ.

Father Maciel never had to account for his crimes, nor did his principal enabler. A few months after the two sets of leaked documents proved his complicity Benedict XVI began a luxurious retirement in the midst of the Vatican gardens, tended by his private secretary and four nuns, and still dressed, head to toe, in the white garb of purity.

Update: the Legion hid money in a tax haven.

According to the "Paradise Papers", leaked in 2017, the Legionset up a corporation in the tax haven of Bermuda to receive the millions that it made from its schools and universities. [25]

Further reading

Daniel J. Wakin and James C. McKinley, “Abuse Case Offers a View of the Vatican’s Politics”, New York Times, 2 May 2010. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/03/world/europe/03maciel.html (a superb summary)

Cindy Wooden, “Cardinal says Legionaries’ reform slowed by criticism of superiors”, Catholic News Service, 13 July 2011. http://ncronline.org/news/accountability/cardinal-says-legionaries-reform-slowed-criticism-superiors

“Abuses Surface at Legion School”, Associated Press, 9 July 2012. http://news.yahoo.com/ap-exclusive-abuses-surface-legion-school-122659372.html

For more than three dozen articles, see the Archive of NCR stories about Fr. Marcial Maciel, especially “Sex-related case blocked in Vatican”, by Jason Berry with Gerald Renner, National Catholic Reporter, 7 December 2001.

Notes (6-15 are translated from Fourest and Venner's book, but renumbered)

* Alexander Markus Homes, Gottes Tal der Tränen (God’s Valley of tears), 2001. The author grew up in a Catholic children’s home in Rüdesheim until 1975. When he tried to publish an account of the abuse the children had endured, he was sued by the Church for slander.

1. “What are the Characteristics of a Religious Cult?” http://www.prem-rawat-talk.org/forum/uploads/CultCharacteristics.htm

2. Brian Ross, “Powerful Cardinal in Vatican Accused of Sexual Abuse Cover-Up”, ABC News, 26 April 2002. http://www.antichristconspiracy.com/HTML%20Pages/ABCNEWS_com_Sexual_Abuse_Allegations_Covered-Up_by_Vatican.htm

3. Ian Fisher, “Vatican Says Mexican Priest Will Not Face Abuse Trial”, New York Times, 22 May 2005. http://www.nytimes.com/2005/05/22/international/europe/22pope.html

4. Rachel Donadio, “Pope Reins In Catholic Order Tied to Abuse”, New York Times, 1 May 2010. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/02/world/europe/02legion.htm

5. Letter from the then Cardinal-designate Velasio De Paolis, pontifical delegate to the Legionaries of Christ, to Regnum Christi, 19 October 2010, “Delegate's Letter to Legionaries of Christ”, Zenit, 23 October 2010. http://www.zenit.org/article-30741?l=english

6. “Group calls for criminal inquiries of disgraced Catholic order Legion of Christ in US”, Associated Press, 2014-01-30 http://www.canada.com/news/Group+calls+criminal+inquiries+disgraced+Catholic+order+Legion/9450180/story.html

7. See the hagiography written by a priest of the Legionaries of Christ, Gonzague Monzon, Un oui unconditionnel, la vie du Père Maciel, Pierre Tequi, 2005, p. 158.

8. Gonzague Monzon, op. cit., p. 164.

9. Jason Berry and Gerald Renner, Vows of Silence: the Abuse of Power in the Papacy of John Paul II, Free Press, New York, 2004, p. 136.

10. Excerpt from the Constitution of the Legion of Christ.

11. The document adds that it isn’t a matter of the number of accused priests or of allegations, those of which parts have been verified. Excluded are the 4,392 priests for which the witness statements agree, but who have died. The report is by the commission of American bishops: A Report on the Crisis in the Catholic Church in the United States (158 pages). Although the report deals very severely with the blindness of the Church, this introspection and this investigation haven’t gone so far as to produce a title that’s clear and direct.

12. See the very good documentary film, of Amy Berg, Délivrez-nous du mal, which tells the story of Father Oliver O’Grady, a predator on children systematically protected by his superiors, who transferred him from parish to parish while the complaints against him accumulated.

13. Gonzague Monzon, op. cit., p. 180.

14. We tried several times to get an interview with members of the legion, or even with their press agency, but in vain. Finally we decided to send a list of questions to the press agency which demanded our CV, a copy of our latest articles, what we were going to say in the book with the right of revision. Those in charge never came back to us.

15. Quoted by Jason Berry and Gerald Renner, op. cit., p. 148.

16. Religious Groups Awareness Network (ReGAIN), http://www.regainnetwork.org/

17. “Mind Control Techniques Used By The Regnum Christi Movement”, ReGAIN, 4 March 2010. http://www.regainnetwork.org/article.php?a=47246075

18. “Decree Regarding Papal Delegate for Legionaries”, Zenit, 24 July 2010. http://www.zenit.org/article-29984?l=english

19. “Legionaries ‘unreformed’, warns priest”, The Tablet, 4 Sept. 2010, p. 38. http://www.concordatwatch.eu/showkb.php?org_id=843&kb_header_id=13061&kb_id=37131

20. "Pope's Legion delegate warns of 'shipwreck'", Associated Press, 27 October 2010.

http://www.google.com/hostednews/ap/article/ALeqM5jd1vcaMNX9nIIEbLroMfw3bSsBcg?docId=1b158a85d4704289973ee985c6cbaeab

21. Nancy Frazier OBrien, “Papal delegate tells Legionaries that reform will take years”, Catholic Herald, 25 October 2010. http://www.catholicherald.co.uk/news/2010/10/25/papal-delegate-tells-legionaries-that-reform-will-take-years/

22. Alberto Patiño Reyes, “Religion and the Secular State: Interim Reports”, International Center for Law and Religion Studies, 2010, p. 511. http://iclrs.org/content/blurb/files/Mexico.pdf

23. La sfida di Benedetto, La Stampa, 21 March 2012. http://www.lastampa.it/_web/cmstp/tmplrubriche/giornalisti/grubrica.asp?ID_blog=242&ID_articolo=5645&ID_sezione=524

[Despite Vatican denials] there are political analysts, who believe that the Pope's visit will exert influence at the time of the vote, including Roberto Blancarte, a researcher at El Colegio de México (public centre for research) and author of El Estado laico (The Secular State) "It's naive to think that neither the Mexican Episcopal Conference, nor the Apostolic Nuncio, neither the Vatican nor the Federal Governmen,t have considered that the dates in which the visiting team fall in the middle of the most important election in six years," says Blancarte, convinced that the presence of Benedict XVI will substantially benefit the ruling party, the PAN since President Felipe Calderon will be the only one who has planned a meeting with the head of the Vatican State.

For more background, see: Rafael Azul, “The Pope’s visit to Mexico deepens assault on the secular state”, World Socialist Website, 21 March 2012. http://www.wsws.org/articles/2012/mar2012/papa-m21.shtml

24. E. Eduardo Castillo and Nicole Winfield, “Pope's Mexico trip clouded by Legion victim's book”, AP, 21 March 2012. http://news.yahoo.com/popes-mexico-trip-clouded-legion-victims-book-103439460.html

25. “Catholic order concedes past offshore holdings in tax havens”, AP, 14 November 2017. http://abcnews.go.com/International/wireStory/catholic-order-admits-offshore-holdings-tax-havens-51140817

The Legion of Christ isn't the only secretive movement over which the Vatican wants closer control. Newer and less well known than Opus dei is the Neocatechumenal Way. For an investigative article on this arch-conservative missionising movement, see “Kiko, the Wrath of God” translated by “Joe C.” Kiko, la Colera de Dios, by Jesus Rodriguez, in the Madrid newspaper, El Pais, 29/06/08. http://church-mouse.lanuera.com/new/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=705&Itemid=854

http://church-mouse.lanuera.com/new/index.php?option=com_content&task=blogcategory&id=13&Itemid=37